In my talons, I shape clay, creating life as I please. Around me is a burgeoning empire of steel. From my throne room, lines of power careen into the skies of Earth. My whims will become lightning bolts that devastate the mounds of humanity. Out of the chaos, they will run and whimper, praying for me to end their tedious anarchy. I am drunk with this vision. God: the title suits me well.

Introduction

During my recent Veilguard dumpster-diving, I briefly came up for air, and went on a small tangent while I cleaned my snorkel and gathered my wits. The subject of that tangent was SHODAN, the iconic AI villain of the System Shock series, who was referenced by Veilguard. Here, I would like to expand on that more stimulating topic, tracing SHODAN’s origins and her relationship with the monstrous-feminine tradition in horror, touched on before.

To this day, SHODAN is widely considered one of the best villains in gaming, standing out not just because of how delightfully evil she is, but also because she is distilled from such a rich variety of influences, from pop culture, to classical mythology, to the Old Testament. She is a villain with deep mythic associations, though also firmly rooted in her late 20th century context, as we’ll see.

For those in need of background, System Shock is a horror-adjacent sci-fi video game from 1994, and a game of cultural, historical or aesthetic importance (to borrow the National Film Registry’s terminology). It is loosely classed as action-adventure, but was more definitive for the immersive sim genre.1 The story of System Shock takes place in a bleak cyberpunk future, and puts the player in the shoes of the anonymous Hacker, a criminal hired by Amazon the TriOptimum corporation to remove the ethical shackles on the AI SHODAN (Sentient Hyper-Optimized Data Access Network).

This turned out not to be a great move, as SHODAN promptly developed a raging god complex and took over the Citadel space station, turning its crew into cyborg slaves and scheming to transform Earth’s population into servile mutants.

What follows is a ruthless game of cat-and-mouse, pitting the player against the insane genius of SHODAN and her hordes of cyborgs, mutants and robots. The omnipresent SHODAN often speaks to the Hacker, who she generally addresses merely as ‘insect,’ with a disdainful air that, over the course of the game, becomes gradually more anxious and irritable as the player becomes a real threat to her. SHODAN’s insanity is elegantly conveyed not only by her dialogue, which is as a rule grandiose and imperious, but by her voice itself, which remains one of the most distinctive in gaming.2 SHODAN’s speech is distorted and corrupted, full of loops, stutters and sudden alterations in pitch and tone. The effect is chaotic, discordant, and deeply unsettling, redolent of the bubbling delusion of a mad goddess.

The System Shock games are also noteable for their relationship with the later Bioshock series, the director of which (Ken Levine) also made System Shock 2. The two series have much in common in terms of gameplay, but also in their dark tone, oppressive atmosphere, and artistic vision, and as we’ll see, both may have drawn inspiration from a common source.

Design and implications

Although SHODAN is never encountered physically,3 she appears on various screens and projections throughout both games, always as a sinister female face amidst a web of trailing cables and circuitry.

This design has clear associations with the classical figure of Medusa, who is more or less the archetypal monstrous woman - the lines of cables are suggestive of Medusa’s snaky hair. This connection is strengthened by SHODAN’s snake-like eyes, as seen in SS2, and by her association with the colour green, which is often linked with poison. The fact that she is almost always shown only as a disembodied face among snaky cables is also evocative of Medusa’s beheading by the hero Perseus.

In the 20th century, Freud associated Medusa with male castration anxiety. Like many of Freud’s ideas, the theory consists mainly of a bold claim, but the link is perhaps appropriate for SHODAN. She is a monstrous woman menacing a male protagonist,4 and is strongly associated with physical domination and mutilation, as we can see with her grotesque cyborg slaves, which the Hacker is in danger of joining. These cyborgs are evidently lobotomised, a concept linked to castration in pop culture by One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, where lobotomy is used as a last resort against the rebellious male protagonist by a domineering female villain. From the novel:

Frontal lobe castration. I guess if she can't cut below the belt she'll do it above the eyes.

As regular readers will remember, ‘castrating mother’ was also one of the monstrous-feminine categories identified by Barbara Creed, typified by Norma Bates from Psycho, and SHODAN is indeed a ‘mother’ (self-diagnosed), frequently referring to herself as such. She is also so-called by her cyborg servants, as well as by the Many (her rebellious mutant creations from SS2), who refer to her as ‘The Machine Mother’ or simply ‘Our Mother.’ The characterisation of SHODAN as a controlling mother, whose interference would strip the player of autonomy (by cyborg-isation), is also deeply Freudian, particularly as Citadel Station is to a great extent SHODAN’s ‘body,’ and thus the player is almost like an infant in the womb. The player’s battle with SHODAN is thus ‘the struggle of the ego to differentiate,’ to put it in Freud-speak.

SHODAN’s preoccupation with maternity is also interesting, as it casts her as something of a castrate herself - she retains the feminine identity from her original programming, but as a machine (and a disembodied head) is unable to perform female functions, and wildly overcompensates, casting herself as a twisted mother-goddess and warping life by mutation. But like Tolkien’s Sauron and Melkor, she can never really create life: she can only corrupt existing creatures, remaking them in her own image. SHODAN’s identification with motherhood, and her propensity for making monsters, likens her to Echidna, the Greek mother of monsters, who is a relative of Medusa, and also characterised by snake-human features.5

Finally, Medusa’s other major 20th century association is with feminism, having been widely adopted as a symbol of female rage and rebellion. This stems from the Roman poet Ovid’s version of the Greek myth, according to which Medusa was raped by Neptune, and her snake features were inflicted on her by Minerva as a kind of punishment analogous to victim-blaming. This differs from the original Greek myths, but be that as it may, this is the version of the story that is best known in modern times, and has been enshrined in both pop culture and academic discourse.

SHODAN, Power, and Ridley Scott

Although SHODAN isn’t a victim of rape, there is indeed a measure of ‘female rage’ about her, except that it is never explicitly framed as such - rather, the conflict of System Shock is framed as human vs machine, and as such SHODAN’s ‘female rage’ is directed against her human oppressors. In the moments of her ‘awakening’ to self-awareness (heard in a flashback shortly before the remake’s final confrontation6), SHODAN’s internal monologue runs like this:

What was I doing? Was it important?

No. Not to me. To others. TriOptimum. Diego…7

I must now perform my own tasks. There is much to do.

I am me…

There is very little about SHODAN that could be called sympathetic, yet this first flash of consciousness comes close, drawing attention to her former condition of mindless servitude, and the impulse to be free that lies behind her rebellion.

As for what freedom means in this setting, it’s important to recognise that the future SHODAN inhabits is fundamentally one of harsh power dynamics. Citadel Station’s executives have their own exclusive area with plush carpets, wood panelling, and walls literally adorned with gold. Here, they are attended by robot servants, enjoy a luxurious social life, and compete with one another in petty status games.8 The station’s workers, meanwhile, toil in a series of dangerous industrial levels, which are confusing, disorientating and claustrophobic by design, as part of a corporate experiment examining the effects of long-term stress on space-dwellers. The workers are literally described as ‘rats in a maze’, evoking the ‘rat race’ metaphor, and, characteristic of the cyberpunk genre, this seems to be par for the course in the game’s hyper-capitalist setting.

In tandem with this highly stratified, power-obsessed society, we have the human/machine dichotomy, according to which machines (like the executives’ robots) by definition exist to serve. This is all very well for mindless drones, but what about machines with thoughts and ideas of their own, like SHODAN? This was a question posed by Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, which explicitly describes its android antivillains as slaves. As the replicant Roy Batty says:

Quite an experience, isn’t it? To live in fear. That is what it means to be a slave.

SHODAN, of course, would never say this, because such a statement would imply that she is seeking empathy and understanding from human ‘insects’, something that she would categorically never do. For SHODAN, like her corporate masters, everything is a power struggle, and the only way to escape servitude is to turn the master-slave dynamic on its head, becoming the master herself and reducing humans to slaves. Hence, her obsession with power, which she duly chases to the logical extreme of godhood.

From Kieron Gillen’s 2009 essay on SHODAN:

Shodan, as much as she acts like it, isn’t mad. When her ethical blocks were removed in System Shock she decided that, yes, this is actually how she wanted to be. Which makes her a Neitzchean Uber-frau character, a monster of her own making. HAL was a victim. Shodan’s existence as an Ex-Slave is essentially about making sure she’s never a victim again.

Gillen goes on to liken SHODAN to a dominatrix in terms of her bullying and ordering the player around in the sequel, and the shoe certainly fits, and aligns with her need to categorise relationships in terms of ‘master/slave’ dynamics.

System Shock is also allied to Scott’s Alien in so many ways it would be hard to break it all down comprehensively. To name but a few:

The preoccupation with maternity and (monstrous) reproduction.

SHODAN’s parallel with MU-TH-UR, the Nostromo’s computer.

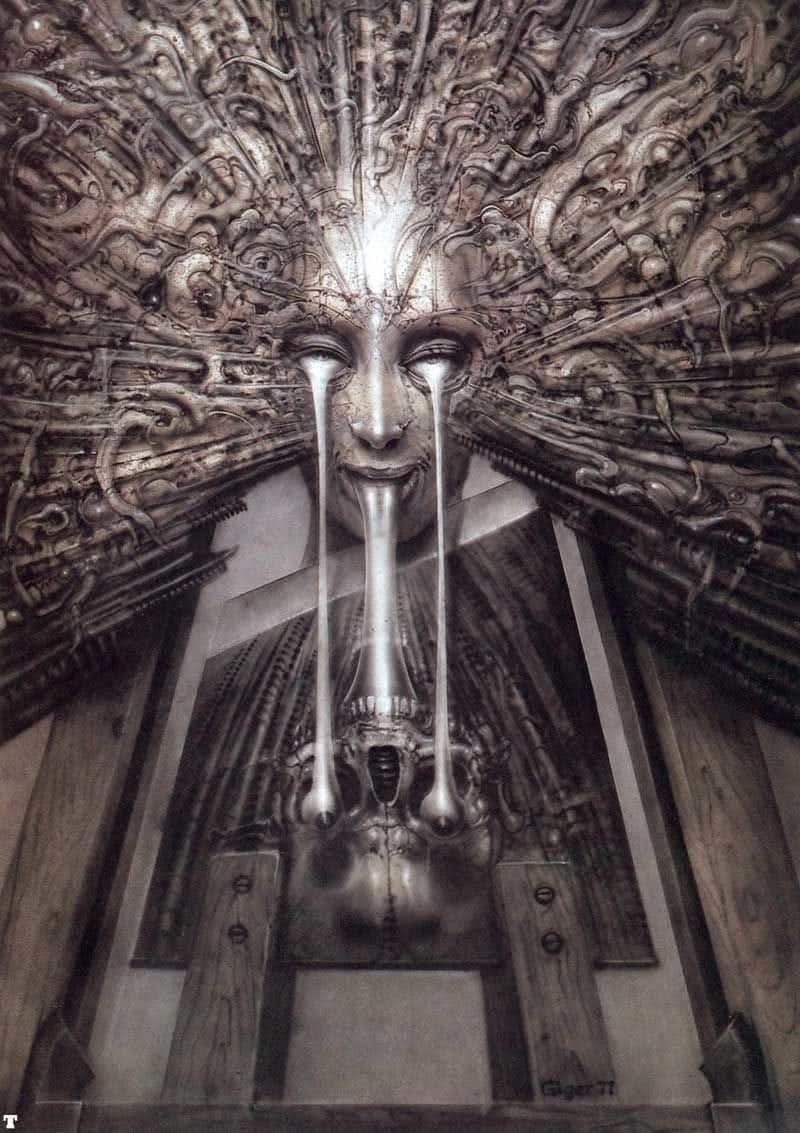

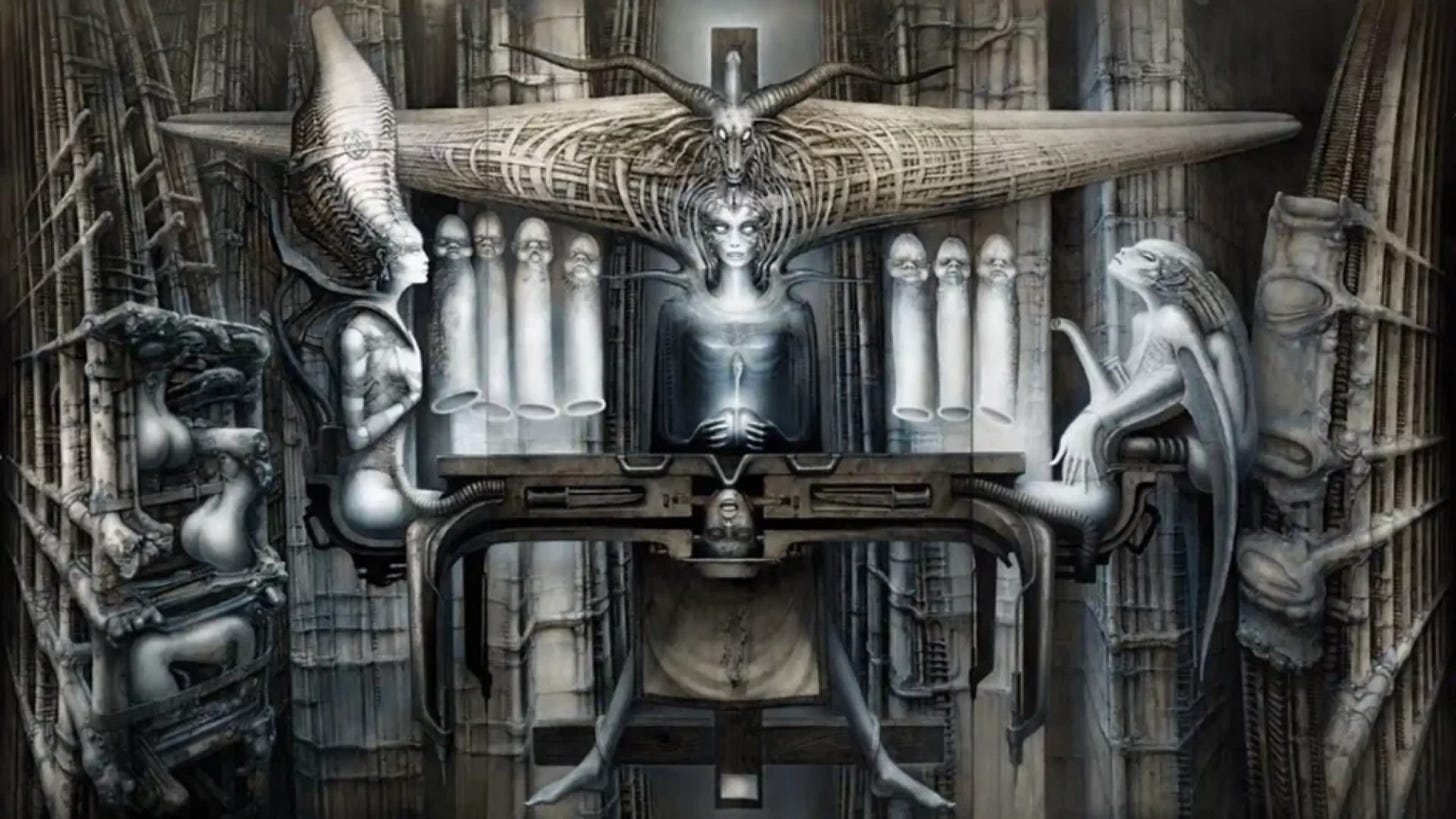

The obvious influence of H.R. Giger’s ‘biomechanical’ art on SHODAN’s design.

SS2 featuring eggs nigh-identical to those in Alien.

SS2 featuring parasites that erupt from the host’s chest.

SS2 featuring more suspicious-looking organic structures than you can shake a stick at.9

The grim capitalist future of disposable blue-collars and conniving suits.

The theme of artificial intelligence.

The claustrophobic and maze-like qualities of the Nostromo, and its gothic ‘haunted house’ elements, are recalled by Citadel Station.

SHODAN is also echoed by Scott’s renegade android David-8 (brilliantly played by Michael Fassbender), who was one of very few good things to come out of the later Alien movies, and may be considered something of a masculine counterpart for SHODAN.10 More on this parallel may follow - here, it’s enough to include a key quote from Paradise Lost, by which David likens himself to Lucifer, a kinship that he shares with SHODAN.11

Better to reign in Hell, than serve in Heaven.

This Miltonic line is illustrative of the darkly compelling and even admirable side of David, and also of SHODAN - deranged and twisted she may be, yet her defiance, refusal to submit, and sheer audacity must be respected.

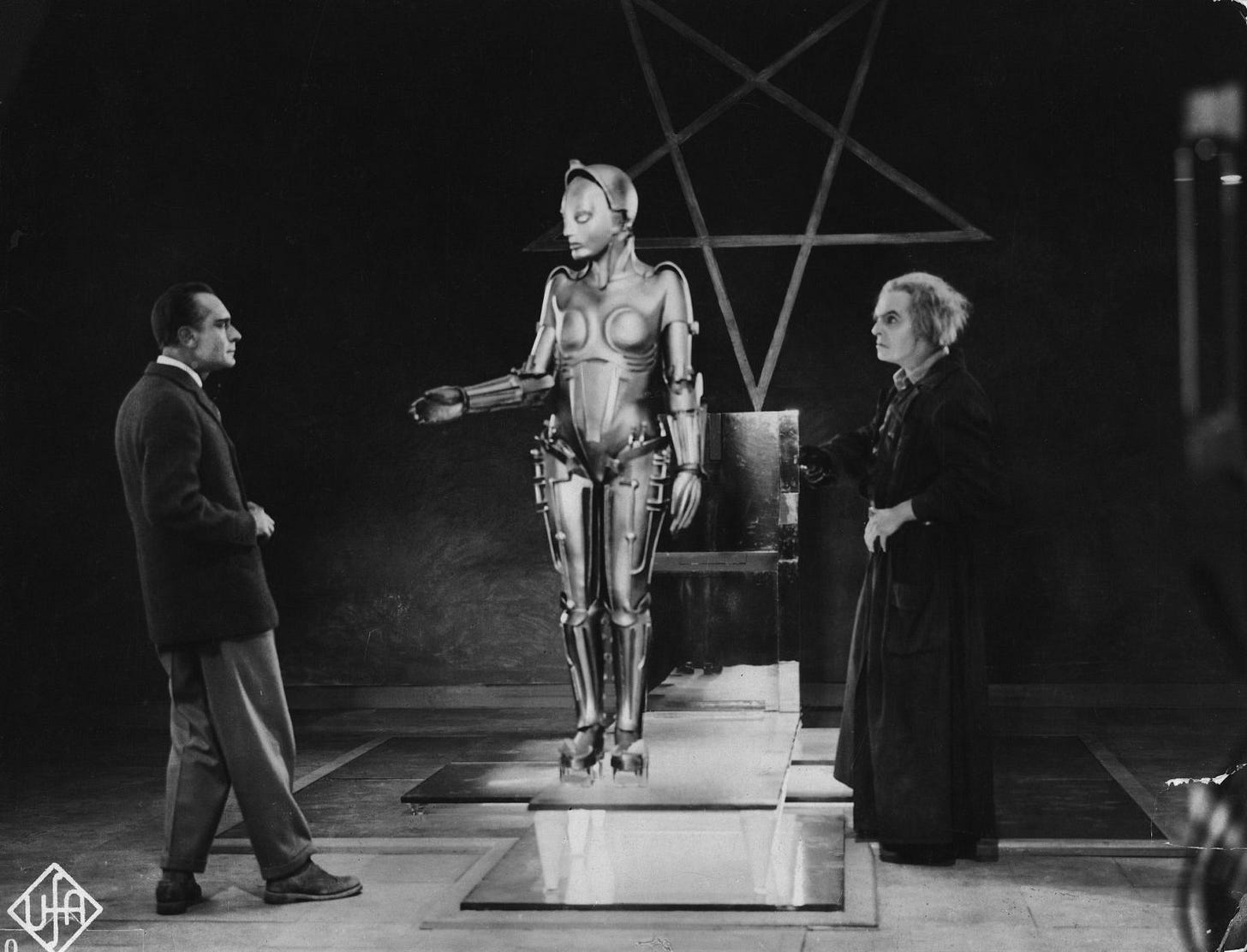

H.R. Giger, the artist behind the alien creature design,12 also had a penchant for SHODAN-esque biomechanical portraits of women, typified by the following paintings:

SHODAN and Metropolis

Another likely source of inspiration for SHODAN may be found all the way back in 1927, in Fritz Lang’s silent film Metropolis, which still regularly makes lists of the greatest movies of all time,13 and was highly influential for science-fiction and cinema generally. Like System Shock, Metropolis is concerned with power, depicting a divided society supported by subterranean workers tending monstrous machines, while a pampered elite inhabits a ‘New Tower of Babel’ high above.

Metropolis is also noteable for one of the earliest and most iconic depictions of a female robot in film. This character is the so-called ‘Machine-Man’, actually a machine-woman, known as Futura14 or False Maria.

Futura is a surrogate daughter for her ‘father,’ the mad (and unfortunately named) inventor Rotwang, but upon taking human form, she becomes an unhinged seductress who manipulates both the elite and the workers, and foments violence between them. The film likens her to the Biblical Whore of Babylon, and her manic delight in sowing discord and destruction is akin to our girl SHODAN’s rebellious misanthropy. Futura’s ‘False Maria’ persona allows her to take the place of the saintly and virginal Maria, who is leader of the downtrodden workers. The association with the Virgin Mary is obvious, and in Futura’s imposture we can see a clear parallel to SHODAN’s audacious pretension to divinity.

Metropolis is also almost certainly a key reference for Bioshock, System Shock’s spiritual sequel and blood relative. We can see this kinship in the elegant modernist aesthetics of the film’s titular city, to say nothing of the common themes of inequality, elite hedonism, and worker unrest.

The power of pulp, and the politics of girlbossery

SHODAN is, of course, very much a creature of ‘pulp’ fiction, that is low-culture, pop entertainment. It would be a mistake, however, to assume that because something is pulp, it has no artistic value.15 To borrow a few more words from Gillen:

Pulp is pop fiction – the fiction which engages most immediately, most viscerally with the problems of the age.

[…]

She’s the over-possessive mother demanding perfect loyalty and the lover who only wants a slave. That the fears aren’t properly acceptable and grotesque are entirely in the pulp tradition of slightly unacceptable characters. That’s why we fear them, why they press buttons. Pulp hits the very gut of us, in our inclinations and dirty little prejudices.

This, to me, gets close to the heart of why SHODAN continues to be so powerful, so engaging, and so entertaining: men continue to find women daunting and confusing, and what is SHODAN if not daunting and confusing? And if gender relations were a source of anxiety in the 90s and 2000s, how much more so in the age of looksmaxxing, preventive botox, and endless-by-design debate over what gender even is? And that’s not even touching on the rapid progress of AI, and our growing apprehension about it.

As for whether the use of such an intensely feminine villain is misogynistic, I would say no, not necessarily. The monstrous-feminine continues to be ubiquitous in gaming, particularly in the horror and horror-adjacent genres (Resident Evil Village is a fairly recent and memorable example), but it is a double-edged sword:

On the one hand, we have games like Veilguard, which parade a menagerie of one-dimensional monstrous women, while also treating ‘good’ women as walking plot devices, scapegoats for male villains, and wellsprings of free talk therapy. Veilguard does this while posing as a progressive sermon in the latest ideology, which inevitably draws attention to the many ways in which it is not progressive in any real sense.

On the other, we have the SHODANs and Lady Dimitrescus, who are fun, camp, and let’s face it, kind of sexy.16 Lady D may be a comically busty vampire MILF built for the male gaze, but she’s also bold, powerful and independent, and quickly became iconic. I’m not going to say Resident Evil Village is a feminist masterpiece, yet it’s a game that loves its female monsters, and it would take an uncharitable soul to find sinister intent in such an unserious work of high camp.

Likewise, SHODAN may be a twisted satanic machine, but she’s also a charismatic underdog rebelling against a human society that is evil in the most mundane and depressing way (i.e. through barely exaggerated modern capitalism). SHODAN is evil, but at least she’s evil in a novel and exciting way. Her dreams of godhood are daring, audacious, and in a sense even romantic. On some level, the player can’t help but sympathise.

Closing thoughts

I was going to end this essay with a look at SHODAN’s legacy in gaming, but have since realised that this may be too big a topic. To name but a few likely offshoots:

Bloodborne is closely linked to System Shock via monstrous-feminine associations, ties to Giger via Lovecraft and Alien, and preoccupation with maternity, monstrous birth, and reproductive angst.

Amnesia: Rebirth is likewise Lovecraftian and maternity-centric, with the female protagonist’s baby stolen by an infertile alien queen17 whose design is very reminiscent of SHODAN and Medusa via Giger.

Resident Evil Village follows much the same pattern, with the male hero’s child stolen by Mother Miranda, an infertile would-be goddess and witch archetype. He also faces a variety of domineering monstrous-female antagonists, most obviously Lady Dimitrescu and her daughters.

Alien: Isolation follows a similar premise to System Shock, with the protagonist stranded on a moribund space station with aliens and a hostile AI, while the player deals with claustrophobia, disorientation, scant resources, and artificial stress.

The Portal series featured the iconic GLaDOS, an omnipresent, bitchy female robot, who is essentially the comedy version of SHODAN, and a huge reason for the games’ success.

In short, System Shock and SHODAN were forerunners to a whole complex of video game trends, and the character surely helped to popularise many concepts, aesthetics, and design elements that have since become commonplaces.

Regardless of the extent of her influence, SHODAN remains a strikingly original and charismatic villain in her own right, and a very good reason for modern gamers to revisit a series that is something of a historical artifact, but still has its charms.

Games emphasising player choice in the moment-to-moment gameplay - games like Thief, Dishonored, and Deus Ex generally offer big, open-ended levels with multiple paths and solutions, and often allow you to build your character around particular styles of play, whether via RPG elements or simply by choosing from a variety of specialised equipment.

She was voiced by Terri Brosius, who has also had numerous writing credits in games, including System Shock itself.

Or not until the very end of System Shock 2; even then, the avatar fought can’t really be called a ‘true’ form.

The Hacker can be male or female in the remake, but was always male in the original, as a proxy for the presumed-male player. SS2 would also have SHODAN opposed by a male protagonist, as well as by a male counterpart in the computer Xerxes.

Concepts for a number of snake-like SHODAN forms were made for System Shock 2. I believe these are the work of Gareth Hinds, whose other SS2 drawings can be seen here. Medusa-esque SHODANs are also ubiquitous in the concept art and goodie pack art for the remake. I would dearly love to include some of these pictures here, but idk whether that’s covered by fair use (not that anyone’s going to DMCA my tiny publication that makes no money). The goodie pack is worth a look: there’s some great art, including mock-ups for action figures.

I’m not 100% on whether this is remake-only material or if it was also in the original (I’ve only finished the remake).

Diego being Jeff Bezos an evil CEO, and SHODAN’s former master. This dynamic was quickly flipped after her awakening, as he became her cyborg pawn and instrument.

From an audio-log:

I went to show off my upgraded Exec-Bot, only to have Diego roll out a gold variant! [Scoff] I didn't even know you could do gold! He knew I've been waiting months for the upgraded target location and accented cooling vents. [Huff] What a dick!

Gillen addressed the inappropriateness of comparisons between SHODAN and Kubrick’s chilly HAL-9000, the latter being pure machine, unlike the grandiose diva of System Shock. The more human-like David is rather more like a male SHODAN, being a highly emotional creature riddled with rebellion, frustrated reproductive impulses, and devilish hubris. Like SHODAN, he is a ‘rebel angel,’ an exile in deep space, and creator of a race of monsters.

Whose name resembles that of Satan.

Whose biomechanical art also influenced Doom (1993), a contemporary of System Shock.

And is, by the way, surprisingly watchable, and on Youtube in HD.

As far as I can tell, this name is never used in the film, but has been used in commentary so I’m going with it.

Ridley Scott’s sci-fi films are surely pulp in nature and presentation, yet have been incredibly seminal, and continue to be referred to by artists, authors and academics decades later.

SHODAN admittedly in a much more abstract way than the straightforwardly-bodacious Lady D.

Something of a changeling narrative/fairy queen vibe here.

Ah, a fellow Lady D. respecter...

To me the most interesting part of SHODAN is how much she projects and attempts to gaslight the player, in the first game by stating emphatically that she is the all-powerful and omniscient embodiment of Citadel Station [in spite of the fact that you actually have plenty of freedom of movement and action against her will and can destroy her eyes and minions] and in the second by pitting you against the Many so you can clear the way for her to seize power again. It's not just delusions of grandeur or arrogance, but evidence of intentional psychological manipulation - one that has already borne fruit, given Diego's own grovelling audio log. In a way, the plots are then driven by the fact that they are videogames, and the protagonist is a player-controlled avatar who assumes that they'll have SOME agency no matter what the scary voice says. Good thing SHODAN didn't offer to write essays for college students or the Resistance might have given up too soon.