Other writings on horror will be linked here.

Spoilers for Interview with the Vampire.

Introduction

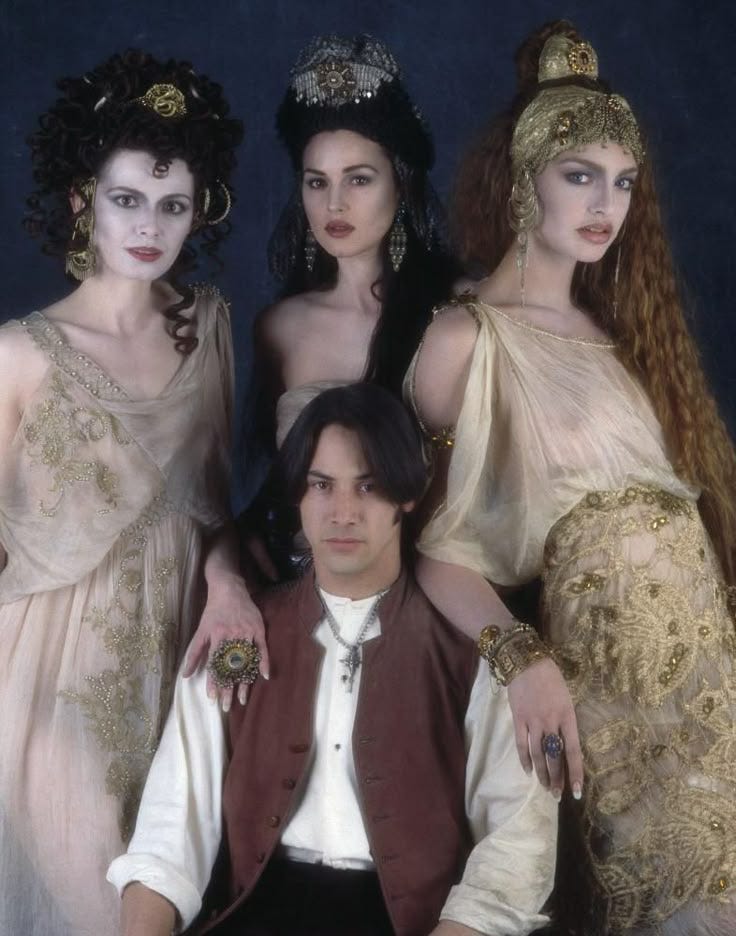

Since Nosferatu, I have been yearning for blood vampire narratives, and as such I have been picking my winding way through the canon of modern vampire media. Most recently, I have gotten a couple of 90s classics under my belt, which could almost be considered companion pieces1 - 1992’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (aka Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula), and 1994’s Interview with the Vampire.

Coppola’s is certainly one of the films of all time, and a fun watch, but you’d be hard-pressed to identify any subtext to speak of. It’s less subtle than Nosferatu2, and also less successful at conveying the dark side of sexuality, which it may or may not be trying to do. It’s certainly conveying sexuality, I can tell you that much.

Interview with the Vampire, on the other hand, is not only a visual and sensory feast, but actually nutritious as well, and for that reason perhaps even more influential, such that it requires little introduction. The 1994 film, adapted from Anne Rice’s 1976 book, was a landmark in the gothic horror genre, and did much to codify the modern vampire story3. However, it passed me by, to such an extent that my knowledge prior to watching it was as follows:

There’s two vampires

One of them gets interviewed

One is called Lestat

It’s very gay

????

Paris

This is all basically accurate, as we will see, but the whole story is a far richer thing, replete with guilt (Catholic or otherwise), terror, codependency, social subtext, and even meta commentary on the genre itself. There’s a lot to unpack in this film, and I enjoyed it immensely.

Dramatis personae

Not wishing to give an entire synopsis at the top, the plot being long, complicated and full of interpersonal chaos, I will instead begin with an outline of each of the main characters and their roles in the narrative:

Louis de Pointe du Lac (played by an especially miserable Brad Pitt4), a vampire who is being interviewed by a journalist in modern day San Francisco. He relates how he, as a young plantation owner in 1790s Louisiana5, became suicidal after the death of his wife and child. Incidentally, this seems to be one of very few details that the 90s film changed to make Louis less gay - in the book, it was the death of his brother that pushed him over the edge, and he never had a wife6.

Lestat de Lioncourt, who sought out Louis while he was in this vulnerable state, and offered to make him a vampire. Lestat is the worst man in 1790s Louisiana (which is saying something), and therefore played by Tom Cruise, the worst man in 1990s Hollywood7. Lestat is utterly ruthless and takes pleasure in killing, making him the worst possible mentor for the guilt-ridden Louis, who struggles with his conscience and lingering humanity throughout the film. He is briefly reunited with Louis in modern times, only to be rejected.

Claudia, an orphan killed by a blood-starved Louis, and resurrected as a vampire by Lestat. Played by a 10-year old Kirsten Dunst in her breakout role. Louis’ guilt over the death of Claudia becomes the basis of a dysfunctional family dynamic between the three - Louis can’t leave Lestat because of his feeling of responsibility for Claudia, meanwhile Lestat encourages Claudia to kill while at the same time spoiling and infantilising her. Eventually, conflict between Claudia and Lestat leads her to attempt to murder him, and she and Louis flee to Europe.

Armand (played by

Puss in BootsAntonio Banderas), said to be the oldest living vampire, who leads a coven of vampires in Paris, the Theatre des Vampires8, where vampires hide in plain sight by posing as an avant garde theatre troupe. Armand becomes infatuated with Louis, and schemes to set his fellow vampires against Claudia, seeing her as a rival for Louis’ affection. After the vampires kill Claudia by exposing her to sunlight, Louis takes revenge in spectacular fashion, setting their coffins alight and coldly hacking them to pieces with a scythe as they emerge9. Armand alone is spared, but rejected by Louis.

Subverting the vampire fantasy

A key idea throughout Interview with the Vampire, which is developed superbly, is that vampirism is NOT, in fact, sexy. This seems counter-intuitive, given the film’s reputation, imagery, and marketing10, yet it is very clear, from Louis’ first night as a vampire, that his condition is a curse rather than a gift, and he quickly comes to recognise it as such. The film is excellent at making the viewer identify with Louis, because like Louis we may feel initially taken in by Lestat’s silver-tongued promises11, and thus we share in Louis’ rude awakening as he is confronted with the horrifying realities of his new existence.

While he is persuading (/seducing) Louis, Lestat describes vampirism as a ‘gift’, and speaks only of eternal youth, beauty, power and freedom: he makes no mention of the endless, irresistible hunger for human blood, or the fact that it is impossible to sate this hunger without killing, until Louis has already made the fateful decision that he can’t take back, and is no longer able to back out of his relationship with Lestat. Thus, although Lestat says that he is giving Louis a choice12, it is clear that he is being dishonest and manipulative: he has chosen Louis because Louis is vulnerable, and the choice he gives him is very far from an informed one.

Throughout the film’s opening sections, we share Louis’ horror at Lestat’s depravity. Interview dismantles the fantasy of vampirism, and instead emphasises the horrible - scenes in which Lestat preys on human victims often begin in an erotic way, only for pleasure to suddenly give way to terror, revulsion and death. This pattern is most obvious in a scene in which Lestat pressures Louis to kill a prostitute, ultimately killing her himself when Louis refuses: the woman’s terrified pleading is pitiful, and it is easy to empathise with Louis and to share his horror of Lestat, with whom he is trapped.

The subversion of the vampire fantasy is taken still further with the characterisation of Claudia, who, though a voracious and remorseless killer (thanks to Lestat’s influence), gradually grows dissatisfied with her existence. Cognitively, Claudia is more like an adult woman than a child, yet she is trapped in the body of a little girl, lifeless, unchanging, and eternally dependent. There is a cruel irony in Claudia’s condition, as the promise of eternal youth is precisely what Lestat used to appeal to Louis, yet in Claudia youth becomes something grotesque, uncanny and a cause of suffering. She cannot even change her appearance in any way, as she discovers to her horror when she tries to cut her hair during an argument, only for it to immediately grow back. Lestat spoils Claudia with dolls long after she has lost interest in them, and to an extent this is what Claudia is to him - a lifeless doll, which he keeps for his amusement, rather than a complete and independent person.

This realisation leads Claudia to demand answers from Louis and Lestat as to how she became a vampire and who she was before. Louis reluctantly complies, bringing her to the house where he found her. Claudia’s bitter love-hate relationship with Louis, who is as responsible for her unhappiness as Lestat, yet who she depends on as a carer and confidant, remains captivating throughout the film.

(I will note here that Kirsten Dunst’s performance in this film is spectacular, and manages to convey the ‘jaded murderer trapped in a child’s body’ concept incredibly effectively, while still retaining tragic and sympathetic qualities. It’s worth watching the film just for her, and it’s no wonder the character became so iconic. Claudia has been referenced by everything from Skyrim to What We Do In The Shadows.)

The film continues to critically examine the vampire fantasy with the character of Armand, the oldest living vampire, whose existence is as joyless as it is endless. Armand tells Louis that the vast majority of vampires ‘lack the stamina for eternity’, but since they do not age, and are forbidden from killing each other, most instead die by suicide. It seems that Louis is Armand’s last hope of a companion, and (per the film’s open ending, distinct from the books) it may be that Armand is likewise doomed to finally die by his own hand, as he is never seen or heard from again after Louis’ rejection.

The story’s preoccupation with the melancholy, un-sexy nightly reality of vampire existence was recognised by the director, Neil Jordan, who said that he was attracted by the novel’s themes of guilt, describing it as:

the most wonderful parable about wallowing in guilt that I'd ever come across.

Roger Ebert had a similar response, putting it thus:

the movie never makes vampirism look like anything but an endless sadness. That is its greatest strength. Vampires throughout movie history have often chortled as if they'd gotten away with something. But the first great vampire movie, Nosferatu (1922), knew better, and so does this one.

It is also interesting that the author seems to have been very aware that this cautionary tale was doomed to fall on deaf ears, because the audience is inevitably attracted and fascinated by the subject of vampirism, and the power/beauty/youth fantasy that the story pushes back against (perhaps vainly) is an inseparable part of that.

This dissonance is represented by multiple characters within the story - Daniel, the interviewer, and Madeleine13, who both beg Louis to turn them into vampires, provoking him to anger and scorn. Louis is unwilling to inflict his curse on anyone else, and when persuaded to turn Madeleine by Claudia (he agrees out of guilt, of course), he is overcome with self-loathing, and says that the act was the death of his humanity. For Louis, the only sin worse than being a vampire is passing that burden on to someone else, and continuing the cycle of cruelty and guilt.

Abuse, exploitation, and social subtext

Interview also does an excellent job at developing the dark subtext of vampirism, which, from its folkloric roots through its cinematic history, has always been more or less associated with sexual abuse in a symbolic way, and therefore with the power imbalances that enable this abuse. Dracula is a count who lives in a castle and pesters young women for a reason.

This subtext is strong in Interview, especially the first act - it’s no coincidence that the vampires, two wealthy white men, begin their spree by preying on the slaves on Louis’ plantation, and are otherwise shown to prey primarily on the poor and marginalised, especially prostitutes from Louisiana’s black and mixed race population. These women are far below them in the societal pecking order, and can be targeted with relative impunity. Although Lestat is said to prefer wealthy white victims due to ‘the snob in him’, most of the victims that we actually see are neither wealthy nor white - in this, his predation strongly resembles that of real-life serial killers, and it’s notable that the novel’s 1976 publication more or less coincides with the peak of the serial killer phenomenon in the United States.

The sexual abuse subtext is also developed very effectively during Louis and Claudia’s first visit to the Theatre des Vampires, as they witness a terrified young woman dragged onto the stage, stripped, leered at and restrained by the decadent vampire performers, and then killed and drained of her blood. The resemblance to a rape scene is hard to overlook14, and is certainly not a coincidence.

The fact that this is done in plain sight before human witnesses15, as is one of Lestat’s first on-screen murders, suggests the societal tendency to either turn a blind eye to sexual abuse, or to fail to recognise it for what it is.

Domestic turmoil and cycles of abuse

Interview also develops themes of emotional abuse realistically in the relationship between Lestat and the vampire family that he has manufactured with Louis and Claudia. When the reporter asks whether Lestat turned Claudia to stop Louis from leaving him, Louis’ response is equivocal, and he suggests that on some level Lestat did love and need both of them. This might be denial on Louis’ part, but it’s somewhat supported when Louis is briefly reunited with Lestat in modern times. Louis finds his ex much diminished, living in squalor and decay, ironically feeding on the blood of rats (as he once mocked Louis for), a vulnerable recluse who is no longer able to take care of himself16. It seems that Lestat never recovered from Louis and Claudia’s escape.

So, Lestat is emotionally dependent on Louis and Claudia, yet for this very reason he manipulates and belittles them, sabotaging their efforts to be independent of him. Louis is deceived into becoming a vampire to meet Lestat’s emotional needs, and is subsequently kept from leaving him by the creation of Claudia, who is bound to them both by Louis’ guilt and by her status as an eternal dependent. Lestat’s enthusiasm for the role of doting father is even somewhat humanising, and leads to his one moment of genuine moral revulsion in the entire story - he is disgusted to find that Claudia, who wants to be an adult woman, is keeping a young woman’s rotting corpse hidden amongst her dolls. Claudia is what Lestat made her, yet even he is horrified by his own creation.

It’s also worth noting that Lestat says more than once that he was never given a choice about whether to become a vampire, and as such there’s a strong implication that he is himself a victim of abuse. We can infer that his trust was betrayed when he was made a vampire, and he never recovered from it. This adds weight and realism to his manipulative behaviour, which seems to revolve around fear of abandonment and an inability to trust his loved ones (if they are loved ones).

Lestat is closely paralleled by Armand, who is also coping with loneliness by trying to create a dependent vampire family for himself. Though he is dismissive of the other theatre vampires, he is accompanied by a young boy, Denis. Denis seems to be a human victim and source of blood rather than another vampire, yet he is under Armand’s protection, and it may be that he intends to turn the boy sooner or later, making him a parallel to Claudia (he is the only other notable child in the film, and he and Claudia are similarly doll-like in appearance). Louis’ rejection of Armand, and his ability to see through his manipulations, therefore represents him having learned from his disastrous relationship with Lestat.

Unanswered questions, Hell, and existential dread

The film is also very successful at cultivating a sense of mystery and uncertainty about its setting, and putting the viewer on an equal footing with Louis and Claudia, who are also in the dark (literally) about the world they inhabit. Like them, we are never privy to the origins or history of vampirism, or how widespread it is, and this brings us emotionally closer to our not-heroes during their long, fruitless search for answers in the Old World. We are as astonished as Louis to finally discover vampires in Paris, and as ignorant of the norms and taboos governing vampire society. This increases the sense of danger when we learn that Claudia, in her ignorance, has crossed two important lines - firstly, by existing as a vampire child17, and secondly by killing another vampire, which is the cardinal sin of vampire society.

This information also raises new questions about Lestat, who though absent in this part of the film, continues to haunt the narrative - was he truly ignorant about vampire society? Or did he withhold information from Louis and Claudia on purpose, to keep them dependent on him?

These uncertainties also feed into the larger mystery of this world’s cosmology, which includes the supernatural, but not necessarily God. Louis (who is presumably Catholic) lives in fear of Hell and damnation, which perhaps explains why he goes on with his unhappy and guilt-ridden vampire life, never daring to attempt suicide. Lestat, meanwhile, questions whether God and Hell exist, and justifies himself via a half-baked ‘might is right’ philosophy rooted in nihilism.

Ultimately, though, Interview offers no answers. Its protagonists live for centuries, yet gain no deeper insight into the dark world they inhabit. There is more than a touch of existentialism in Louis, who is forever introspective, indecisive, and tortured with doubts. Armand believes this to make him the ideal companion, as Louis embodies the troubled spirit of the present age.

Closing thoughts

Interview with the Vampire is not just a great film about vampires - it’s a great film about people. There is more than a hint of social commentary in the depiction of predatory vampires who target the most vulnerable and least protected in society, and do so in plain sight, knowing that onlookers will turn a blind eye.

It also very realistically depicts dysfunctional family dynamics: Lestat deceives and hurts those he most depends on, out of fear that they will leave him, and Louis is never able to find the strength to stand up to him independently, only doing so through Claudia’s agency. Later, he finds the strength to reject Armand and avoid being drawn into another abusive relationship, although once again this has to do with Claudia, or rather the loss of Claudia - Louis is only able to be strong when he has nothing to lose, hence Lestat’s need for Claudia to stabilise their relationship in the first place.

Interview has a ‘sexy’ gloss to it, but unlike Coppola’s Dracula this is not to be taken at face value - Interview’s vampires are appealing only at first glance, but sleazy and predatory underneath. The film does much to critique and subvert the vampire fantasy, which is both the initial attraction from the audience’s point of view, and Lestat’s means of reeling Louis in. The film emphasises the terror and suffering that vampires inflict on their human victims, and also the anguish suffered by vampires themselves.

Interview with the Vampire asks what would drive a vampire to pass on their curse, and the narrative readily supplies an answer to that question: loneliness. A vampire is lonely, so he makes another vampire, and another, and on and on it goes. Everybody needs somebody, even the damned, but this need only leads to more and more suffering.

And Coppola’s Dracula did directly influence Interview. Quoting director Neil Jordan: ‘Up to that point, Francis Ford Coppola with Bram Stoker’s Dracula, he introduced opulence and theatricality. Normally, before that one, I always thought of vampire movies as cheap, cobbled together, brilliant use of minimal resources. Francis made it this epic, didn’t he? So when I was given the opportunity to make Interview with the Vampire, I thought, "Oh, it would be really great to expand on that epic sense of darkness and to give these characters huge, kind of romantic destinies and longings and feelings.’

Regular readers will remember that I did not consider Nosferatu particularly subtle. Good? Absolutely. Subtle? Noooooo.

The gamers among you will find a lot of commonalities with Vampire: The Masquerade. Apparently the original tabletop game’s designer deliberately avoided reading Anne Rice’s books until very late in development, though Rice likely influenced VTM indirectly via other films that inspired the game.

Six months of night shoots in London during the winter will do that. They made the man a method actor against his will.

:/

I should note, however, that the film is otherwise pretty textually gay. Although Lestat and Louis are not explicitly shown to be intimate, they are described in the same terms as you would describe a couple. Louis’ later almost-kiss with Armand also makes his orientation very clear, such that you would have to do some pretty advanced mental gymnastics to read it any other way. This was fairly boundary-pushing for the 90s, and Anne Rice even wrote a female version of Louis at one point, fearing that the film wouldn’t get made otherwise.

Between this and Eyes Wide Shut, I’m not convinced that Tom didn’t spend the 90s reverse method acting his real life.

Brilliantly parodied by What We Do In The Shadows.

10/10 sequence, very cathartic.

Oprah Winfrey famously walked out of the film in disgust after ten minutes, considering it immoral material. I can understand her reaction, as the film initially appears to revel in vampirism, but this is quickly turned on its head.

After all, we wouldn’t be watching a vampire film if we didn’t think vampirism was at least a little bit sexy/cool.

Lestat repeats the ‘choice’ line verbatim to the reporter at the end: it seems that he is running a script, and is evidently never entirely sincere.

A young woman bereaved of a daughter, who Claudia is cultivating as a carer and companion, as she anticipates that Louis will leave her for Armand.

An obvious parallel would be A Clockwork Orange, which featured a similar scene in a theatre.

They assume it is part of the performance.

This is evidently his motive for turning the reporter into a vampire at the end of the film. Having been rejected by Louis once again, and unable to cope by himself, he needs a new companion.

(it is forbidden to turn children into vampires; this is one line that even the depraved members of the Theatre des Vampires will not cross)

Great analysis as always, and the memes you used are hilarious 😂

Even thought I haven't watched the movie, this aligns pretty well with my reading of the novel. While I don't particularly like bringing up an authors life when analyzing their work, i think it's interesting to relate the lack of clear answers in the story to Rice's own struggle with her faith and the loss of her daughter, which she admits was the inspiration for Claudia.

Something that stands out to me is how race and slavery is so integral to the story. At least in the book, Lestat's treatment of Louis and Claudia is often compared to slavery, which is curious because the story is largely uninterested in Louis' own role as a slave master who feeds on his "property". I wish the movie had expanded on that, though it seems it doesn't do much better on that front than the book.

I highly recommend checking out the show! Not only does it tackle the problem of racism in the original, but it also gets rid of the subtext regarding Louis and Lestat's relationship.

Great post. I agree that Interview and Bram Stoker's are intimately bound together, and am looking forward to your upcoming post on Dracula. *wink*

For my part, the reading of Interview, in particular the movie adaptation, that sticks in my mind is as an analogy of fame, talent, or success. Particularly going into the 90's, the depiction of a lifestyle that the masses can see only for its power and propensity for sexy parties, but almost invariably becomes an isolating purgatory for those 'lucky' enough to experience it, rings especially true. Like vampires, famous mega-star actors [like, oh, say, Brad Pitt and Tom Cruise] look like they have it all, can do anything they want, live forever, and yet are eternally subjected to the threat of annihilation, most of all by their own hands. The pathologies that feed and eventually eat away at these creatures are powerfully depicted - an insatiable hunger for escalating stimulus, an inability to relate to mortals that drives them to each other, an instinct for grooming and control, and so on. The fact that there's even a child actor analogue, forced into early maturity and thrust into a Bedlam of depravity, but eternally burdened by her own youth, hits pretty hard as the proceeding decades create whole stables of former Nick and Disney stars that are then unleashed on society. [to say nothing of the fact she has more than a bit of Shirley Temple going on]

As far as the homoeroticism [which is indeed excellent] angle, I think it is not just ahead of its time for being a level of depiction that was progressive for a movie in the early 90's, to say nothing of a novel from the 70's, but is even more powerful for its grappling with the darker and more complex manifestations of homosexuality in western culture. Again, the inherent loneliness, the urge to identify and groom the 'exceptionals' away from mortal society, fear and control dominating relationships, and the looming specter of self-destruction all have just as much to do with the realities of being a part of gay culture in the era before Peak Rainbow Flag Saturation as they do with my earlier reading about celebrity. And, as an unabashed but not naive fan of Tom Cruise, I wouldn't be surprised if deep down he could identify with both of those readings, whether or not he'd ever admit that. Look at the guy today. You're telling me he's 60?! Maybe he skips the subtext part and just got bit for this role.

Again, looking forward to your posts on Bram Stoker's Dracula and What We Do in the Shadows. *wink wink*