Fire and Ice (1983): My Problematic Fave

Bakshi and Frazetta's Sword and Sorcery romp

Introduction

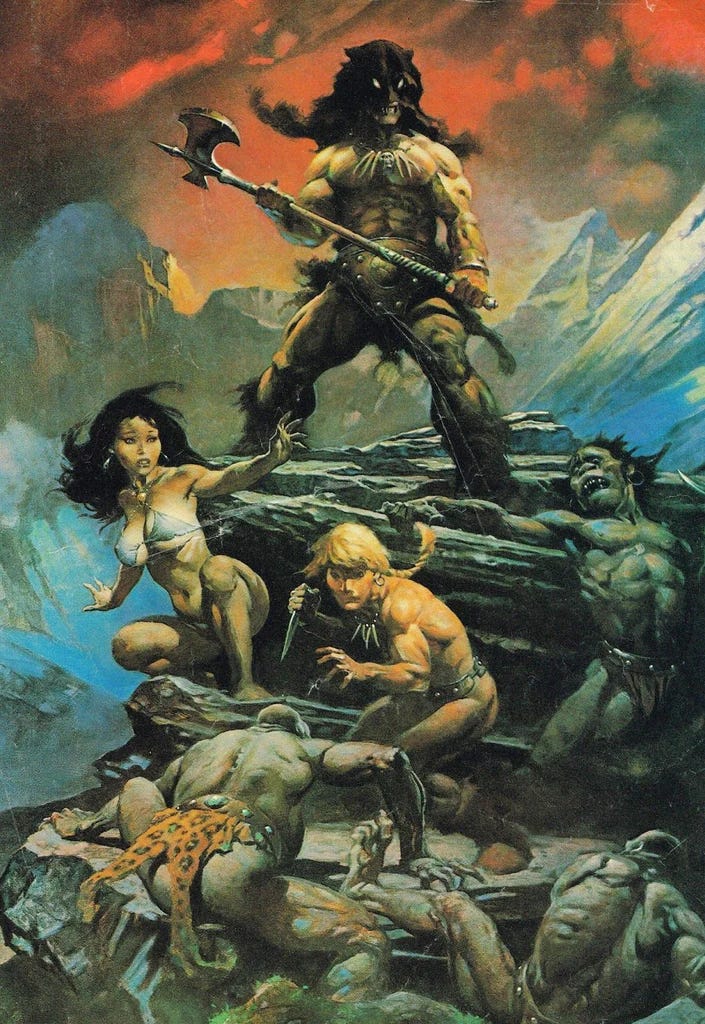

For those not au fait with commercially unsuccessful fantasy from the 80s, Fire and Ice needs some introduction. This was Ralph Bakshi’s third fantasy animation after Wizards (1977) and The Lord of the Rings (1978), both of which have been covered here before. It was also his first, and only, collaboration with the legendary artist Frank Frazetta, best known for his Conan the Barbarian paintings. As most readers will know, a Frazetta moodboard would consist largely of pictures of battle axes, snakes, dinosaurs, ape-men, muscular heroes wearing very little, and busty women somehow wearing even less.

Fire and Ice is basically just all of that, and more. Add in witches,1 more ape-men, wolves, the greatest lava castle you’ve ever seen, pterodactyl-riders, an aggressively gay-coded sorcerer, his overbearing mother, the Watcher in the Water, and a deuteragonist who lives for revenge, and that’s Fire and Ice. It’s an experience.

The film’s script was penned by Gerry Conway and Roy Thomas, both prolific comic-book writers who had written Conan stories for Marvel, and it is very much a comic-book movie, with far more emphasis on action and spectacle than intricate plot. This is, predictably enough, one of many things that critics were scathing about at the time. The film made very little money, and remains largely unknown, although I will be making the case that this is not necessarily a reflection of its quality. Looking at the contemporary response, it seems to me that critics fundamentally missed the point of Fire and Ice, and measured it against the wrong set of criteria entirely. It’s worth noting that the film was made on a tiny budget of $1.2 million, and should be weighed accordingly.

It is also very gruesome and violent, with a lot of bloodshed, threat, and many inventively gruesome magical and mundane deaths. In a way, it’s very refreshing to see an old, traditionally-drawn 2D animation that is so clearly and unapologetically not for kids, and refrains from many of the tropes of Western animation. This is very much in line with Bakshi’s stated mission to push boundaries and broaden the scope of what animation could be.

Synopsis

As usual, it’s best to begin with an outline of Fire and Ice’s story:

The film opens with some brief narration re. the central conflict between the frozen citadel of Icepeak, and the opposing volcanic Firekeep. Icepeak is ruled by Queen Juliana, a powerful witch, though the real star villain is her son Nekron, a languid white-haired sorcerer and the source of Icepeak’s power. Firekeep, meanwhile, is ruled by the benevolent King Jarol.

Following this exposition, we are shown the fate of a village in the path of the expanding Icepeak. Buff blond warriors man the defenses with spears and loincloths, but the walls shatter under the force of the advancing glaciers. The warriors are overrun by Icepeak’s ape-man soldiers, and slaughtered. It is here that we’re introduced to our hero, Larn, a basic blond dude experiencing the call to adventure in the form of angry hominids trying to murder him. We also catch a brief glimpse of Darkwolf, his future ally, who is aura-farming on a nearby cliff.

Larn is able to escape the ape-men by playing dead, and then manages to arm himself and kill one who is attempting to loot him. A frantic chase follows, with several ape-men killed in the struggle; this all looks fantastic, due to the fluid rotoscoped animation. Unlike previous Bakshi films, there is no attempt to blend live-action with animation - characters appear fully and continuously in their animated forms, but the rotoscoping technique gives their movements a lifelike quality, which helps to ground these larger-than-life characters.

From here, the action moves to Firekeep, where Queen Juliana has sent ambassadors, supposedly for peace talks. In fact, the ambassadors have been sent to abduct Princess Teegra. Here, we meet Teegra, who is just ridiculously sexy and spends about 90% of her screentime being abducted by ape-men. True to form, she is abducted by ape-men, who also kill her pet panther and her hot Egyptian tutor. It’s a disaster.

Meanwhile, Larn narrowly survives an encounter with wolves, aided by the mysterious Darkwolf, who keeps his distance and doesn’t introduce himself. He finds himself in a ruined and overgrown city, where he notices a weathered statue that the viewer recognises as Darkwolf.

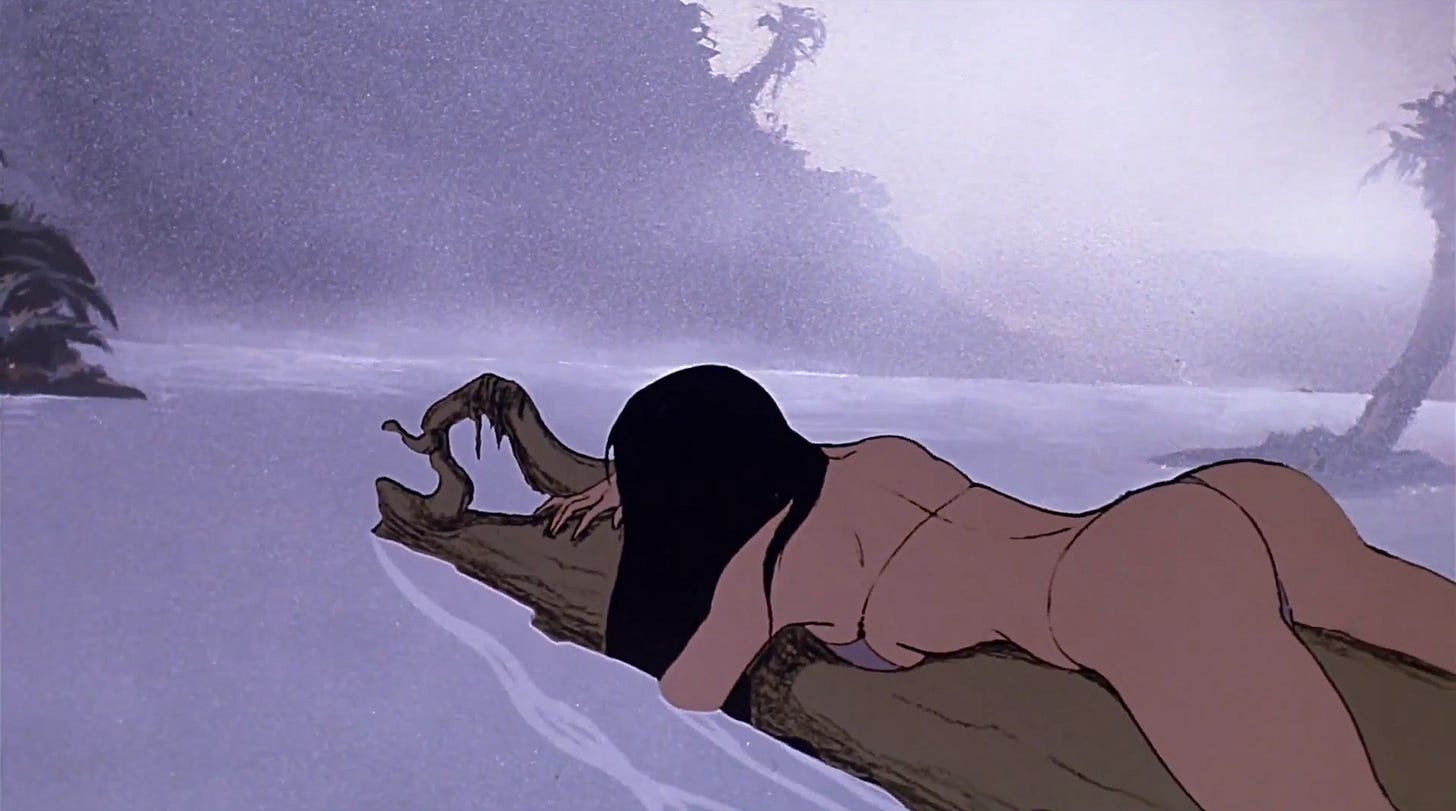

Elsewhere, Teegra manages to escape her captors by diving into a river while bathing, and while the ape-men give chase they are set upon by a giant lizard that rushes out from the water. Afterwards, the ape-men magically communicate with Juliana, reporting the princess’ escape, and Juliana proceeds to remotely strangle the leader to death Darth Vader-style, wrenching him bodily into the air with a ghostly noose.

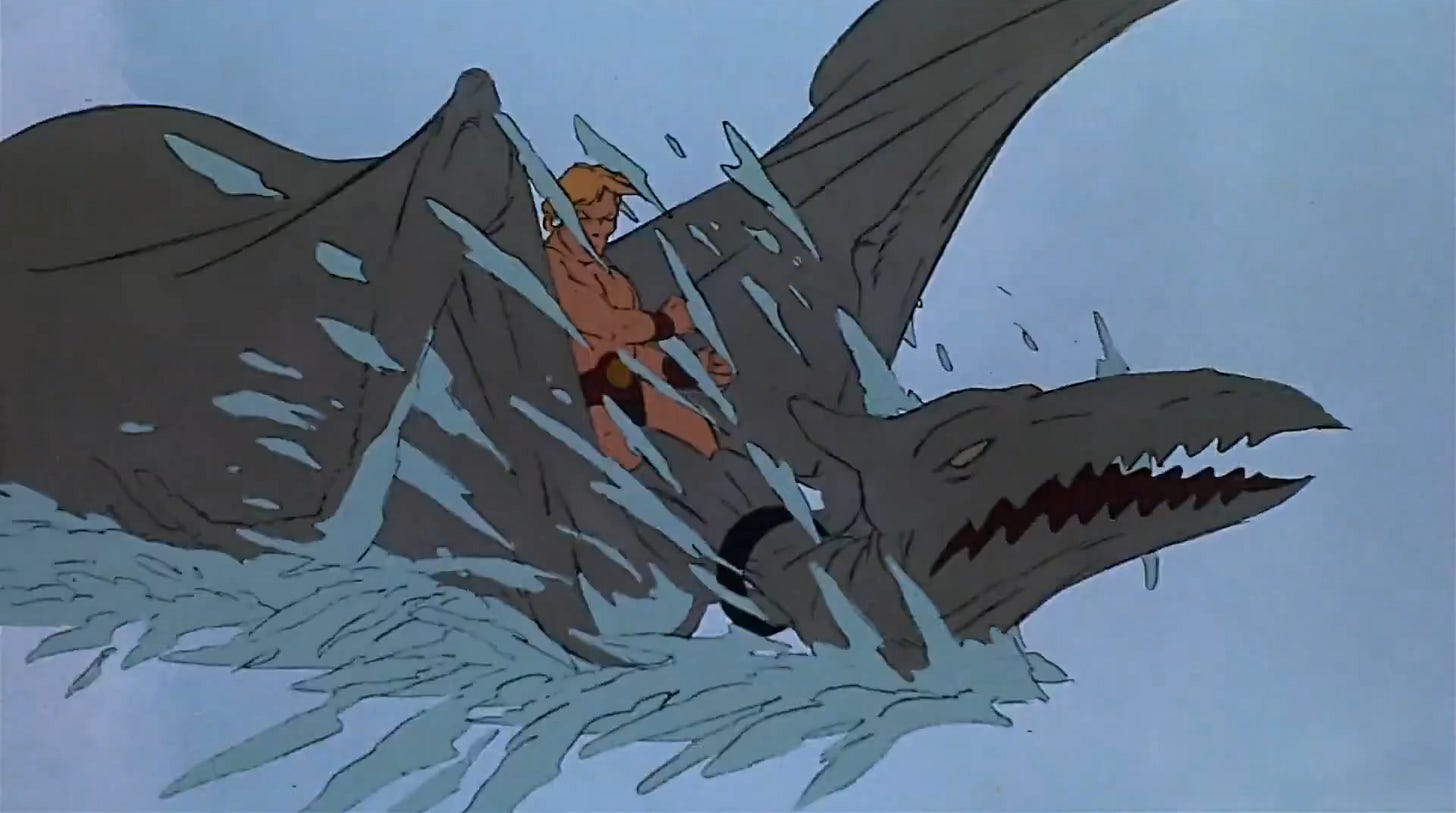

Larn and Teegra meet in the ruined city. There is a flirtation over what seems like a few days, before Larn is attacked by a tentacled sea-monster, and Teegra is recaptured by the ape-men. Larn is found unconscious and revived by Darkwolf, with whom he joins forces. Darkwolf, it transpires, is motivated by a vendetta against Nekron and Juliana - the details are not divulged, but the statue in the ruins implies that Nekron destroyed Darkwolf’s people.

Meanwhile, Teegra attempts another escape, stealing a dagger and stabbing an ape-man to death. However, she is chained to him, and has to drag his body with her. The escape is aided by Darkwolf and Larn, who attack the ape-men by night. Darkwolf proceeds to rack up an impressive kill-count with his battle axe.

Teegra is discovered by another, larger, and even uglier ape-man, who brings her to his witch mistress. The witch connives to sell her to Juliana, but Juliana treacherously has her minions kill the witch and take Teegra by force.

The witch’s charred skeleton briefly awakes to tell Larn which way the ape-men took Teegra.

The king sends his son, Prince Taro, on a mission to Icepeak to negotiate Teegra’s release. Here, the brooding, Targaryen-like Nekron makes an impression, and uses his magic to force Taro and his men to kill each other. It’s a gripping scene, establishing just how powerful, dangerous and unpredictable Nekron is. The corpses are unceremoniously dumped in a frozen pit.

Teegra arrives at Icepeak, where Juliana presents her to Nekron as a possible bride. Nekron rejects her in disgust, as he apparently has every previous prospect - we’re starting to get the idea that Nekron doesn’t like women very much, and oh boy, that’s going to be confirmed. Teegra is summarily dumped in the corpse pit, where she finds her brother’s body.

Larn and Darkwolf go to Firekeep and ask for the king’s help in rescuing Teegra. The king agrees, and our heroes assault Icepeak at the head of a host of dragon-hawk (pterodactyl) riders.

Larn is briefly captured by Nekron, who declares that Larn ‘intrigues’ him, and proceeds to undress and challenge him to the most homoerotic duel this side of Berserk. After defeating him with magical aid, Nekron has Larn taken to a cell, anticipating future duels (and maybe not just duels). Teegra vacates the corpse-pit and breaks Larn out.

During a climactic, pterodactyl-intensive final battle, Darkwolf confronts Nekron on a giant hand,2 and by sheer force of will manages to break through Nekron’s magical defenses and bury an axe in him. Firekeep erupts, and without Nekron’s magic to sustain it, Icepeak is destroyed.

Teegra asks Larn to spare a wounded ape-man, which he does, symbolically ending the cycle of revenge, and the lovers look up to see Darkwolf Death Dealer-posing in the distance one last time.

Reception and analysis

What is probably emerging pretty clearly from this story breakdown is that Fire and Ice is fast-moving, eventful, and fundamentally action-centric. To quote a contemporary critic:

If you love comic books but can't bear the unnecessary bother of turning pages, Fire and Ice [...] may be for you. It would help if you were a sex-obsessed 12-year-old boy, but it isn't essential.

The comparison to comic books is apt, considering who wrote the script. However, the scathing and dismissive tone is less helpful, and is unfortunately representative of the contemporary consensus. Gene Siskel admitted the film’s beauty, but called its story slow and predictable, while another critic dismissed the story as ‘standard.’ Still others called it a ‘pointless animated mush,’ and termed its (partial) nudity ‘fetishistic.’3

These kind of comments, however, seem to be missing the point: they are not assessing Fire and Ice on its own terms, or even on suitable terms, but instead according to criteria which are totally inapplicable. Fire and Ice is very clearly and un-self-consciously a work of pulp fantasy, not a drama film. Its cast is composed entirely of stock characters with very simple motivations, and the story does indeed follow a ‘predictable’ formula. However, that is not necessarily a bad thing!

Because the story is straightforward, it moves quickly; because the characters are simple, embodying familiar archetypes, they are both vivid and easily legible. Fire and Ice requires very little in the way of exposition or introductory scenes, and because of this, every scene is purposeful and to the point. The film is only 81 minutes long, a full forty minutes shorter than Star Wars, a similarly tropey adventure film, and nearly fifty minutes shorter than Conan the Barbarian, the John Milius film of the previous year which gave Fire and Ice impetus.

So, even when we compare like with like, Fire and Ice’s perceived deficits in story and characterisation seem very explicable, and a justified trade-off for spectacle, which it more than delivers on. It seems almost redundant to add that serious drama films tend to be vastly longer: The Godfather is able to deliver such an intricate story in large part because it is more than twice as long as Fire and Ice.

Could Fire and Ice deliver a more complex story in 81 minutes? Of course, but only at the expense of action and spectacle, which happen to be the two key characteristics of the film and its source material. When you read Conan stories or look at Frazetta paintings, you don’t come away from them amazed by the complexity and nuance of the material. Indeed, a huge part of Conan’s effectiveness as a short story protagonist is his simplicity and predictability - you can drop him in any situation and he will do and say barbarian things, and this constancy makes him effective as a common thread. Likewise, the fact that the characters he encounters embody familiar archetypes limits the need for cumbersome exposition, expediting the adventure.

What is true of Conan is also true of Fire and Ice. The film is characterised by constant forward momentum, and above all by efficiency. Darkwolf, who is arguably the stand-out character, is illustrative of this: he introduces himself with very few words, but he is a vivid and well-defined character, and although little is directly stated about him, much can be inferred from hints. The statue in the ruins, and his vendetta against Nekron and Juliana, point to a tragic past, and given how overgrown the ruins appear to be, there’s a sense that Darkwolf has been single-handedly waging a guerilla war against Icepeak for a long time. It’s worth noting that First Blood introduced the character of Rambo to the popular consciousness the previous year, and like Rambo, Darkwolf is a troubled lone survivor skilled in ambush tactics, traps and trickery.4

Symbolically, Darkwolf is very much a ‘lone wolf,’ with a wolf-skin mask covering part of his face, and it is no coincidence that he saves Larn from wolves near the ruins. His dialogue is much in keeping with this animal motif, referring to Juliana as a ‘bitch’ and to the ape-men as ‘Nekron’s dogs.’ The sense is of a civilised man reduced to an animal, driven by survival and revenge. Notably, Darkwolf is always drawn with glowing animal-like eyes without pupils, which adds to his mystique: because we can’t tell where he’s looking, there’s a heightened sense of danger and unpredictability about him.

This human-animal theme is seen throughout the film. Teegra has her black panther, sleek and feminine; Juliana sails in a ship adorned with carved spiders, creatures symbolic of schemers; Larn wears a tribal necklace with a fang; the Firekeep warriors have their dragon-hawks, and wear winged helmets; and the ape-men occupy an uncertain category between man and beast. Only Nekron lacks a clearly legible animal motif, with only a strange chimeric demon figure on his throne. This is perhaps appropriate: as a white-haired magical prodigy, he is marked out as different.

The -isms

Of course, any modern assessment of Fire and Ice would be incomplete without considering its racial and gender politics, which are, uh, interesting, to say the least. From a certain point of view, the film does kind of achieve the Holy Trinity of being racist, sexist, and homophobic, though not uncomplicatedly so.

For instance, it’s hard not to notice that the ape-men all have very dark skin, and spend a lot of time menacing white women.5 They’re also called ‘subhumans’ in the script, for… some unfathomable reason. Now, Bakshi satirised racists in a number of his films, depicted brown heroes regularly,6 and was also notable for hiring minority artists,7 so on balance it seems unlikely that Fire and Ice was meant as an elaborate Trojan horse for racism. Still, I don’t think many modern artists would stake their fortunes on a movie about black-skinned ‘subhumans’ contrasted with a blond, blue-eyed Ubermensch, and maybe that’s for the best.

Speaking of women getting menaced, there’s the question of sexism, which is raised by, among other things, Teegra’s general existence. She’s a fairly ineffectual and extremely sexualised damsel, who is captured about four times, or, on average, once every twenty minutes of runtime. In her defence, she attempts escape several times, sometimes successfully, and kills a number of ape-men. She is, however, basically naked all the time, and every Teegra scene is ludicrously porny, with the camera constantly centred on her breasts and buttocks.

This is par for the course with Bakshi and Frazetta, who are both, to put it mildly, big admirers of the female form - put them together, and it was absolutely inevitable that they would spend their time avidly drawing boobs, and consider the development of the character they were attached to an afterthought. Further, the film’s female representation beyond Teegra consists largely of evil witches, one of whom is also someone’s overbearing mother. Basically, it’s the kind of film where women are either sexy, antagonistic, or both, which is pretty typical of 80s sword and sorcery.8

Finally, there’s the question of homophobia, which is raised by the fact that Nekron is a villain so gay-coded he loops all the way around into not even being coded - he’s just textually gay at this point. There simply is no heterosexual explanation for Nekron undressing for his duel with Larn, calling him ‘intriguing’ after so pointedly rejecting Teegra, and calling all previous female prospects ‘sluts.’ His uneasy relationship with Juliana also invokes the trope of the gay man with an overly close relationship with his mother, and his brooding energy is that of an isolated, frustrated man lashing out at the world. Even his albinistic character design plays into this, contrasting him with the bronzed heroes, and physically marking him out as different (or queer, if you will).

Nekron’s affinity with magic is also suggestive - in Robert E. Howard’s stories,9 and in the various myths that inspired them,10 magic tends to be highly female-coded, and male sorcerers are depicted as effeminate, villainous and transgressive figures, contrasted unfavourably with virile barbarian heroes who overcome obstacles by brute force.11 This dynamic is epitomised in the confrontation between Nekron and Darkwolf, who overcomes Nekron’s magic by sheer strength of muscle and will.

Be that as it may, it must be said that Nekron is a charismatic and memorable presence, and, as with all good villains, there’s something cathartic in his unhinged antics. Moreover, his credentials as a troubled white-haired magician place him in a fantasy niche more often populated by complex and morally ambiguous outsiders.12 Given his obvious resentment of Juliana, and her intense dynastic preoccupations, there’s a sense of Nekron as a kind of unhappy Habsburg prince, bred for greatness and put on a throne whether he wants it or not.

Closing thoughts

Although Fire and Ice is in some ways typical of the sword and sorcery of its time, it is atypical in terms of its overall quality, and the sheer creative spectacle that is made possible by its animated medium. Whereas Conan the Barbarian and the like had to deal with the limitations of practical effects, Fire and Ice has the most menacing ape-men you’ve ever seen, and similarly vivid pterodactyls, river monsters, and volcanic eruptions. Its fluid animation and beautiful painted backgrounds give the whole production a luxurious quality that belies its tiny budget, and the action is grippingly well-done.

While the film was soundly rinsed by the critical consensus at the time, it seems to me that it deserved better. The charges against Fire and Ice were overwhelmingly that it was what it was (a short, small-budget adventure film), and not something it could never have been (a long, sophisticated drama film). It seems particularly unfair to complain that a short-ish animated film resembles a comic book, given that both are fundamentally similar mediums, visual rather than textual. And whether Fire and Ice is to your taste or not, it’s hard to deny that it excels as a piece of visual media, communicating efficiently through images while using words sparingly.

This is most obvious with Darkwolf and Nekron, both magnetic presences whenever they are on screen, so that their inevitable clash is thoroughly satisfying. They may be familiar types, but there is nothing wrong with the familiar done well.

Buxom, of course.

If you are thinking of Berserk, it might not be a coincidence. There’s also a white-haired gay-coded villain, and a dark vengeance-driven antihero with a dog/wolf motif. Hmmmmm…

These quotes are all gleaned from the reception section on Wikipedia. I think it’s worthwhile responding to these, since anyone curious about Fire and Ice is likely to check the page, and if they do their impression of the film will be overwhelmingly negative.

He also warns Larn that fighting Nekron means learning to live with pain - Rambo, of course, is a traumatised veteran, living with both physical and mental pain, and is a sobbing wreck by the end of First Blood.

See: the works of Robert E. Howard. There’s a lot of profoundly racist stuff in there, particularly his horror stories, but also the Conan tales, the worst of which do indeed compare black people to apes, and generally feature them as dim-witted henchmen of lighter-skinned sorcerers, much like Fire and Ice’s ape-folk. It’s not a great vibe.

Including his version of Aragorn.

(including Brenda Banks, the first black female animator, who worked on Fire and Ice)

See the incident in Milius’ Conan when the sexy witch turns into a monster and tries to kill him during the act. Freud would have a field day with this ultra-masculine stuff and the ambivalence about women that lurks between the lines.

Howard, by the way, may have been closeted. His frequent descriptions of muscular, vital, tigerish men with smouldering eyes are… not particularly heterosexual, to say the least.

See Norse culture, in which the word for a male witch and the derogatory word for a gay man were the same. See also the Scythians, who had a sort of eunuch-esque ‘third gender’ priestly/wizardly caste, distinct from a warrior elite.

Think Thor and Loki in Marvel, or more tangentially Maximus and Commodus in Gladiator.

Elric of Melnibone, Geralt of Rivia, Griffith from Berserk, and many Targaryens fall into this category.

James Gurney worked on this film as his first big job. His buddy Thomas Kincade got him in as a background painter, and Jim wasn't terribly good at landscapes. He learned real quick! He has lots of retrospective behind the scenes stuff on his blog. If you don't know who James Gurney us, look up the Dinotopia books. :-)

Wait a minute... ruined cities, a wolf-headed ally, a snake-themed sorcerer with mommy issues, and an unending horde of demi-human servants? Maybe Berserk wasn't the only thing FromSoftware have been ripping off all this time!