More on video games can be found here and here.

Introduction

Papers, Please is a tiny indie production from 2013, which also just happens to be considered one of the greatest video games of all time. At release, it was showered with awards and universally lauded, and the game has more than stood the test of time: by its tenth anniversary, it had sold more than five million copies, and it still gets hundreds of new Steam reviews every month, 97% of which are positive. It was created by a solo developer, Lucas Pope, who designed, coded, and built it pretty much from scratch, including the art, music and sound. The dizzying success of Papers, Please is rendered still more impressive by the fact that, as the name implies, it’s a game about paperwork.

Yes, paperwork. Passport control, specifically. Papers, Please puts the player in the shoes of a passport inspector on the border of Arstotzka, a bleak, non-specific fictional country evocative of the USSR. The inspector has no particular qualifications for the job, but has won a ‘labor lottery,’ which is apparently the state’s way of assigning work to those in need. The inspector is crowded into a ‘Class 8’ apartment, also assigned by the state, along with his wife, son, and several dependent relatives, and it seems that he is the only one lucky enough to have a job. His family’s fate therefore depends on him alone. Times are hard in Arstotzka, and they’re only going to get harder.

Every morning, the inspector dutifully takes up his post in a building surrounded by concrete, barbed wire, and armed guards. Here, he faces an endless stream of people seeking entry. Immigrants, asylum seekers, journalists, diplomats, traffickers, terrorists, smugglers and spies, the inspector must process them all. Every new face in front of your desk is a potential imposter, and the only certainty is uncertainty, but one thing’s for sure: you’ll have been party to some human rights violations before the month is out.

Setting and presentation

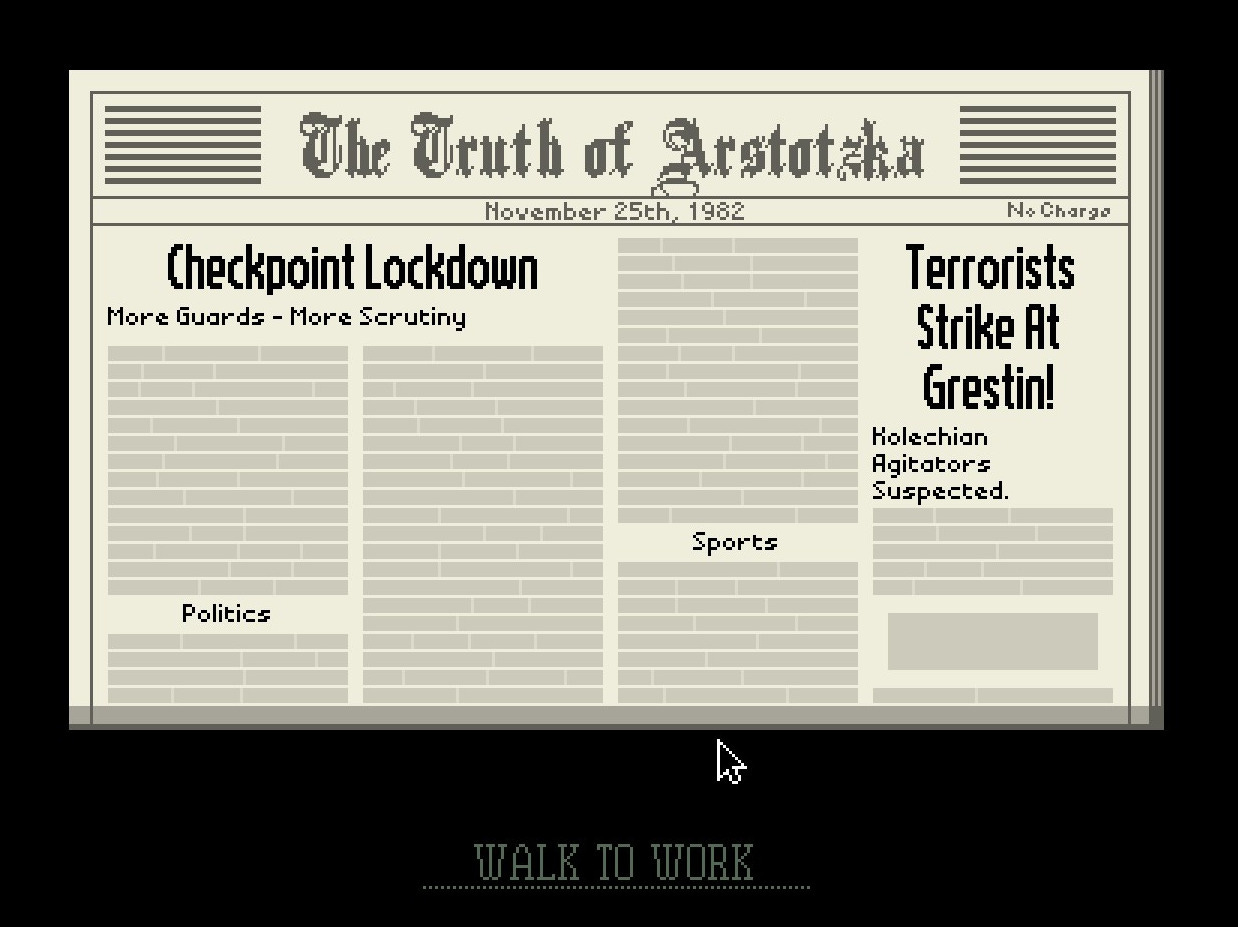

Much of the power of Papers, Please lies in its simple yet evocative graphics and its sparing worldbuilding. Although we have a sense of the wider world through the newspapers, through the names of various countries, and through snippets of incidental dialogue, the only part of the world we actually ‘see’ in detail is the border checkpoint itself. This is a boxy little building in an expanse of monotonous grey concrete resembling a car park, sometimes cracked and pitted by bombs, with a loudspeaker on top to call in the next applicant.

Because we never see much of the wider world, there is a sense of the tunnel vision and alienation imposed by the inspector’s circumstances: work dominates his life, and for all intents and purposes, his desk is now his entire world. The checkpoint is also a kind of microcosm, as it becomes the centre of political events that may determine the country’s future. There are regular terrorist attacks from the neighbouring country of Kolechia, which was recently invaded by Arstotzka, though we have little insight into what actually happened or the reasons behind the continuing conflict. Equally, we are in the dark about the mysterious revolutionary organisation EZIC - indeed, we don’t even know what, if anything, EZIC’s name stands for. These omissions of detail are both clever and deliberate - by limiting our knowledge, the developer forces the player to see this world through the eyes of the inspector, an ignorant prole in a police state where information is tightly controlled.

Characters in Papers, Please are represented in a few ways: from a distance, we see the entrants as tiny black silhouettes packed together like swarms of ants, devoid of individuality. This creates an emotional distance between the player and the entrants, although this distance is mutable, since characters are also seen face-to-face in front of the officer’s desk. The game’s stylish character design still stands out as excellent. Whereas many games emphasise young and good-looking characters, the people of Papers, Please tend to cluster around middle-aged, and their haggard, careworn faces emphasise the poverty and hardship in this slightly-too-lifelike setting.

Although Pope stressed his preference for keeping the setting vague and avoiding exact analogues, for instance omitting the word ‘comrade’ as far too obviously Soviet,1 it must be said that the setting remains highly USSR-coded. We see this in the Russian-inspired musical motifs,2 in the Slavic names and syntax, in the hammer emblems on various seals and papers, and in the opaque and arbitrary operation of the regime. The in-game date is also 1982, which inevitably makes us think of the autumn years of the Berlin Wall.

Even so, the use of a secondary setting has surely helped the game to age as well as it has: the 2020s have been a more than usually authoritarian decade so far, and as such the messaging of Papers, Please still feels relevant, in a way that it might not if it was explicitly a history lesson about East Germany or Yugoslavia. Going after defunct and discredited regimes can feel like beating a dead horse, or worse, a cathartic diversion from problems more current and closer to home. Papers, Please wisely sidesteps this.

Finally, there is the checkpoint’s interior, which is dominated by the inspector’s desk space, where the player can drag around various items and documents. This is surely the greatest desk in gaming,3 and feels very much like an actual desk, in that you will naturally find yourself organising it like a real work-space, keeping specific things in specific places, and as the pressure builds, you will also inevitably find yourself losing important things under the endless stream of paper that crosses your desk, and losing valuable time as you frantically shuffle papers to find what you’re missing.

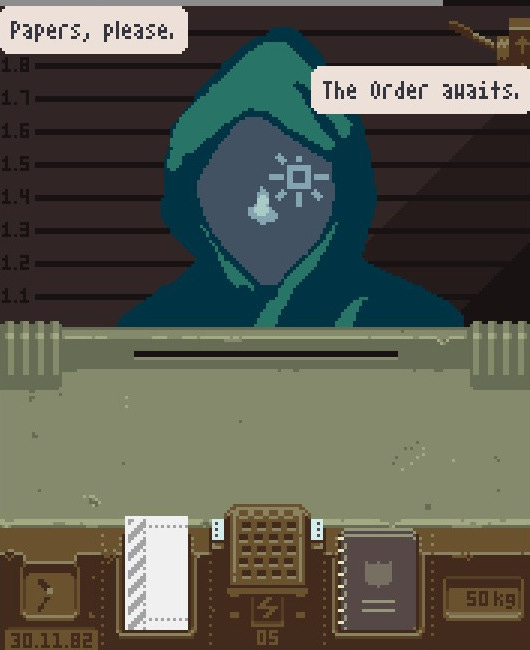

The inspector can only see entrants through a layer of protective glass with a narrow slot through which papers (and bribes…) can be passed, and metal shutters are automatically dropped when an entrant is being detained. These precautions add to the atmosphere of fear and distrust at the border, and give a sense of just how dangerous the inspector’s job can be.

Narrative and design

In terms of gameplay, the object is, initially, simple - the inspector is given a set of rules, and has to make sure that each entrant’s papers satisfy the conditions for entry. This basically amounts to looking for discrepancies, such as:

The passport photo mismatching the entrant.

Mismatched names or numbers.

Mis-spelled place names.

Passports being issued by the wrong city or district.

The entrant being the ‘wrong’ gender.

The entrant being the wrong height or weight.

The entrant giving wrong information verbally.

The first fews days on the job are relatively easy, but as the days and weeks go by, the inspector’s work becomes exponentially more difficult. Every day brings new complications, new demands, new stipulations and new exceptions. Suddenly, passports alone aren’t good enough, and must be supported by entry permits, identity supplements, work permits, citizen ID, vaccination certificates, and more. The inspector must compare faces against lists of wanted criminals, must keep the keys to a weapons locker in sight in case of terrorist attacks, and must pore over bleary images of strip-searched suspects. In short, every day comes with fresh hardships, the greatest of which is always money.

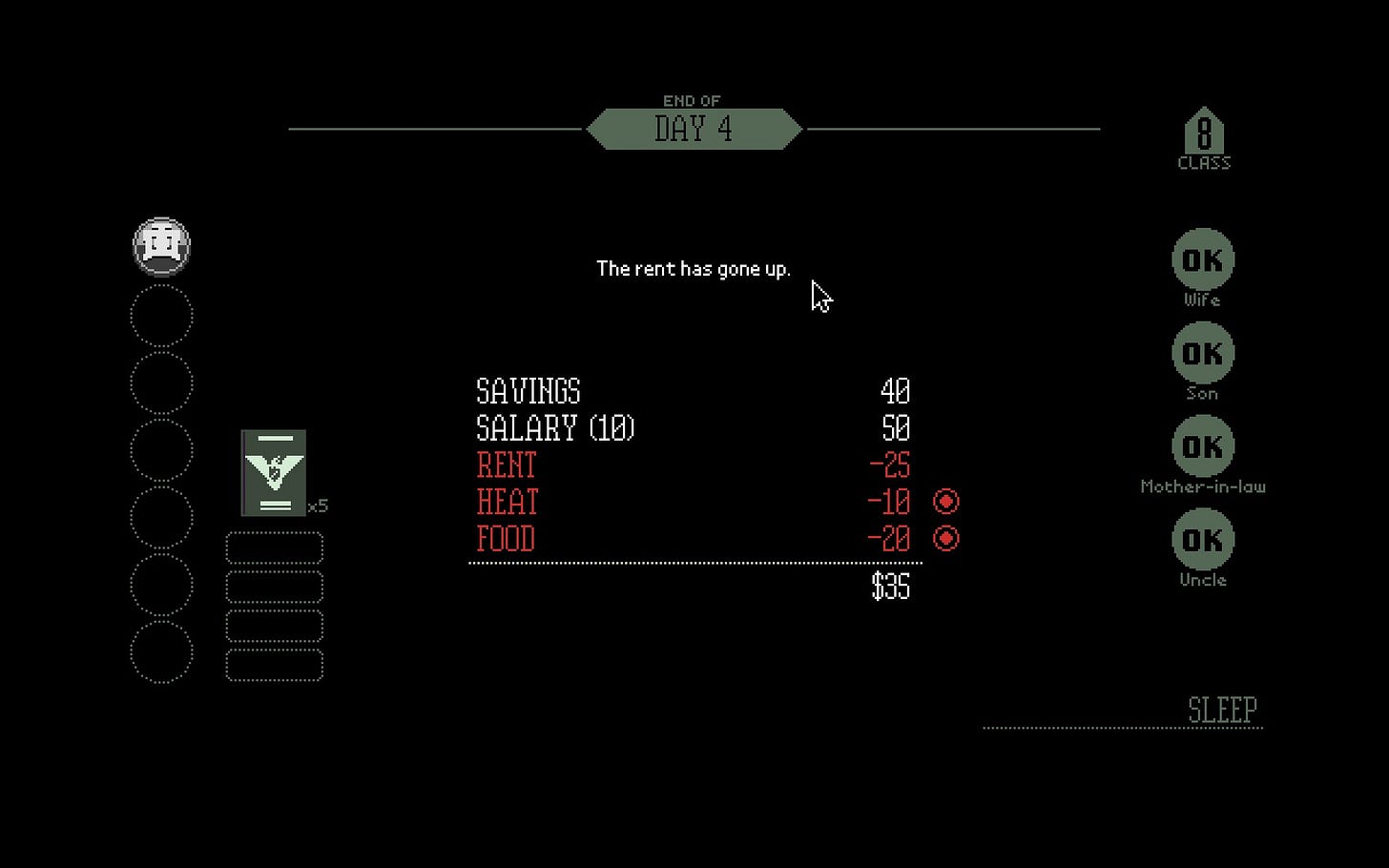

Money is a constant and pressing need in Arstotzka. Your family is counting on you, and while the job gets harder every day, the pay remains the same. The inspector’s wage depends on how many people he manages to process each day, but as the documents pile up, processing takes longer, and mistakes are inevitable under pressure. Past a certain threshold, these mistakes start to cost money, as pay is docked. As such, the inspector simply can’t afford to have scruples. Most players will soon find themselves taking bribes from smugglers and wanted men, simply because there’s very little choice if you want to keep your family alive and well.

About a week in, the inspector will be approached by one of the soldiers, Calensk, who offers him a bonus for each person detained. Detention is often an option, but seldom a requirement: the option can be triggered by anything from typos to having the wrong genitals, and most of the time, there’s no penalty if the inspector simply declines these people entry and lets them go free. Thus, Papers, Please requires the player to look people in the face and coldly decide their fate, and gives you a strong incentive to do harm to them. We don’t know what ‘processing’ of detainees involves, although we can surmise it’s not good.

Detaining people for a few extra credits doesn’t necessarily feel great, but neither does letting your son go without food and heat, or abandoning your niece to an uncertain fate because you can’t afford the adoption fee. Whereas many games present moral choices in a superficial way, and offer no real practical or emotive incentive to do ill, Papers, Please is more true to life: it puts the player between a rock and a hard place, and simulates the brutalising effects of poverty and coercion. If you want to survive, you have to be part of a oppressive system, and if you’re part of that system, you’re going to end up doing harm to your fellow man. The game even gives you a very good rationalisation, in the form of the inspector’s family: surely, your first responsibility is to your family?

The game alternately erodes the player’s sense of empathy, and builds it up again. The sporadic terror attacks on the checkpoint are initially shocking (who expects terrorism in a game about paperwork?), but after one or two, the player is less shocked, and more irritated by the inconvenience: an attack means cutting the day short, and those precious lost work hours mean lost income, which matters far more to the inspector than the lives of the faceless soldiers being blown up. Later in the game, when the inspector is armed with a tranquiliser rifle, the dynamic shifts again: now, the player is not merely indifferent, but ghoulishly pleased to hear motorcycles and alarms, because it means the opportunity to earn a ‘sharpshooter bonus.’ The Arstotzkan regime has not only game-ified work: it’s work-ified war.

Likewise, even the most kind-hearted player may feel a stab of vicious pleasure when the ‘detain’ option pops up, because a detention means money, and money is everything. It’s all too easy to dehumanise the endless stream of incomers, and the constant pressure of the clock cultivates a feeling of callousness towards these wretched supplicants. The clock doesn’t stop when they ask questions, argue or complain, and when time is money, it’s all too easy to resent every wasted second, especially when the inspector must answer the same questions over and over again after a new rule is implemented.

But the player’s resentment isn’t only directed at the entrants: it’s also directed at the regime. The constant, arbitrary changes of the rules, which hurt the inspector and his family, build up a strong sense of resentment towards the unseen and unaccountable decision makers. The inspector must also deal with a petty and tyrannical boss, who docks pay for the most minor infractions, yet demands that the player let in his girlfriend without documentation and take the financial hit.

It seems that nobody really believes in Arstotzka’s rules or respects the system, or even bothers to pretend to, least of all the middle-management officials. The closest thing we see to patriotic feeling is from a couple of football fans who proudly support the ‘Arstotzkan Arsekickers’ and give the player a banner to hang on the wall. But really, there’s very little to be patriotic about - everyone’s poor, everyone’s on the take, and revolution is closer than it seems. The regime has resorted to brute force, and citizens’ passports are seized while they are subject to political ‘audit’ by a STASI-like ministry.

Accordingly, the EZIC organisation is plotting to bring down the regime, and the inspector can become involved in their schemes by passing messages between operatives, poisoning a regime spy, and confiscating IDs to pass on to EZIC imposters. But EZIC isn’t to be entirely trusted either: the organisation is mysterious, its methods bloody, and to go all-in on EZIC is to sacrifice everything.

At a key point, the inspector has the option to give his life to the cause by committing an assassination for EZIC, but doing so is not necessarily the right thing to do: one dissenting EZIC agent suspects that the target isn’t even a threat, and if the inspector gives his life, he can do no more good for the cause, and his family is left to an uncertain fate. On the other hand, if he spares the target and continues to hold out, he can either flee the country or put his trust in the coming revolution. The EZIC storyline is thus a very lucid cautionary tale: for things to get better, the inspector must be willing to take personal risks for the good of society, but to give everything to society is dereliction of his equally important duty to his loved ones.

The one thing the inspector must absolutely never do is put his faith in the regime. Cowardice and toadying is not rewarded: to rat out EZIC is to sign your own death warrant, and prompts a swift, premature, and well-deserved game over, as the inspector is deemed guilty by association. Power does not have your best interests at heart, and the game expects you to learn that lesson quickly, and to learn it well.

NPCs, choice, and difficulty as a narrative device

With escalating violence, a looming audit, and the constant pressure of poverty, the rules must be followed closely, but not religiously. It is in the inspector’s power to make exceptions for desperate entrants, and mercy is always a possibility. Bending the rules necessarily comes at a financial cost, but this makes (optional) acts of compassion all the more meaningful, especially when the fates of recurring NPCs hang in the balance.

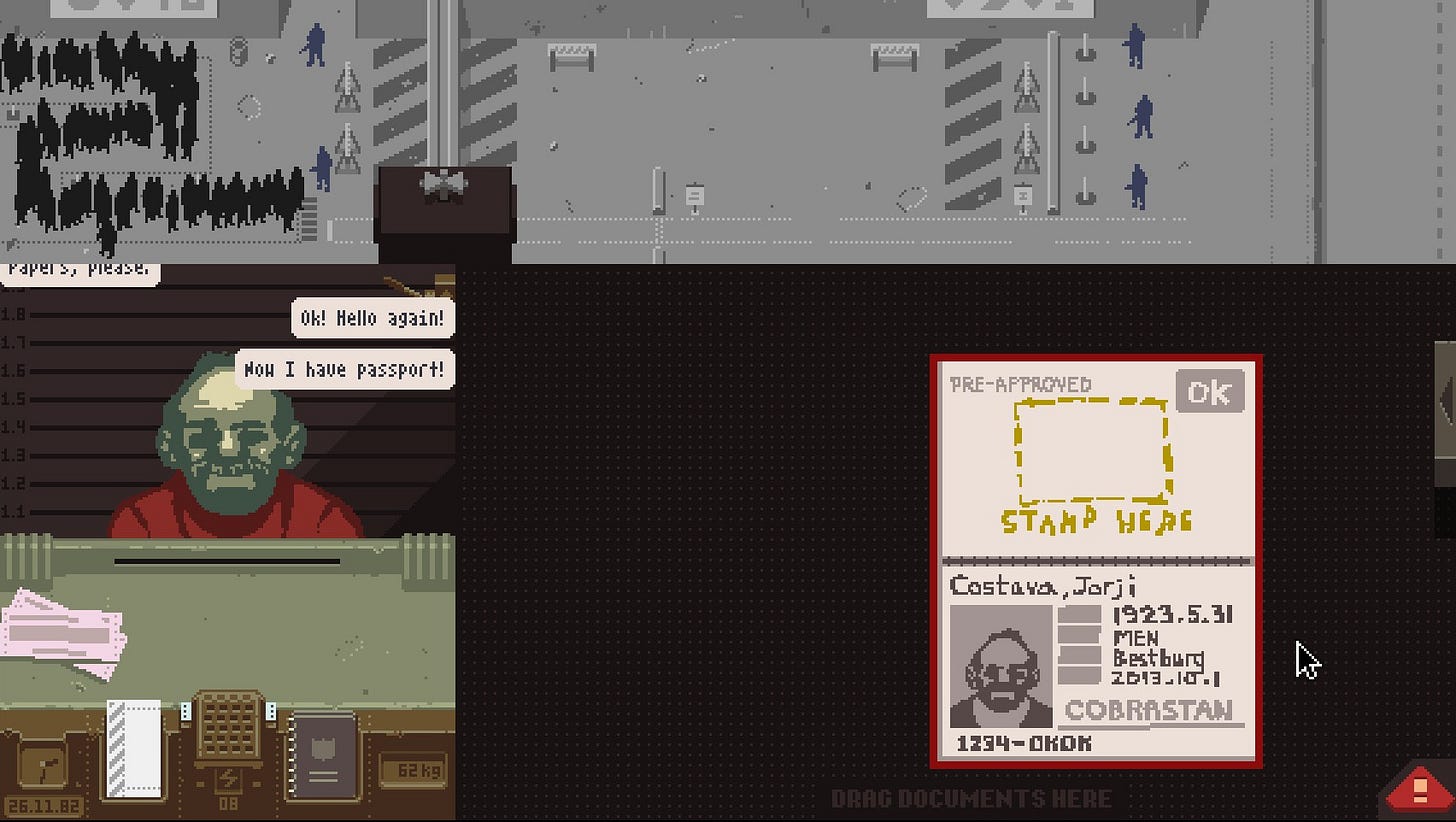

One such character, who is particularly memorable and beloved by fans, is the cheerful Jorji Costava,4 who continually tries to deceive the inspector with comically amateurish forgeries. He becomes a drug smuggler, and, if you play your cards right, a reliable source of bribes. Jorji may be a crook, but he’s a thoroughly good-natured crook, and the closest thing to a friend the inspector has at the checkpoint. He offers crucial help later on, and shares a generous sum of money at a pivotal point in the narrative even if the player hasn’t helped him at all.

Another key recurring NPC is Sergiu, a soldier at the checkpoint and veteran of the war in Kolechia, who asks you to let in his long-lost sweetheart from the other side of the border. Sergiu is marked as an individual by being shown in green in contrast to the other blue soldier silhouettes: this can lead to a particularly gut-wrenching moment if you fail to save him during a terror attack shortly after his reunion with his love. It’s a great moment of ludonarrative harmony,5 because it is entirely possible to save Sergiu, but only by fast reflexes and excellent shooting: thus, if you fail, you feel a real sense of guilt, knowing that you might have saved him if only you had been a little faster on the draw.

These are only two of many special NPCs that the inspector may help or hinder, and helping them feels worthwhile, even if it usually comes at a personal cost. Papers, Please is a story about navigating harsh circumstances, and the difficulty of the game pushes you to make morally murky decisions. Yet the game is not unreasonable in terms of its expectations of the player: a patient and attentive gamer can attain a happy ending without becoming a monster, and indeed it is arguably easier to bring about a full-blown revolution than to scrounge up enough money to flee the country with your family intact.

It must be said that the game’s difficulty is remarkably well-balanced, which speaks to both shrewd design and rigorous testing: it’s difficult enough that you feel involved in the inspector’s struggles, and are pushed to cut corners you might not in other circumstances, but easy enough that it’s accessible to average human beings, which is, after all, what the inspector is. This delicate balance is surely a major factor in the game’s success, being challenging enough to be absorbing and effective, but still accessible for a majority of players.

The game’s relative brevity (about five or six hours for a complete playthrough) is also welcome in a world where contemporary games, thanks to ever-increasing budgets and cost of admission, are often padded out with undue bloat. Papers, Please wisely adopts the attitude of ‘less is more,’ and neither spins out its narrative to the point that impact is lost, nor pushes its gameplay formula too far.

Closing thoughts

Thanks to its clever gameplay, stylish presentation, and universal themes, Papers, Please has aged incredibly well, and it’s really no surprise that it continues to do numbers on Steam. The game depicts life under tyranny very effectively, and makes the most of its interactive nature to not only explore various tensions and dilemmas, but to personally immerse the player in them. The inspector is torn between duty to family and duty to society, but ultimately, as the most optimistic ending shows, the two are not mutually exclusive: for things to get better, ordinary people like the inspector must be prepared to take risks and make sacrifices, yet total self-sacrifice is not an inevitability. The revolution doesn’t need martyrs to reach the tipping point - it just needs enough ordinary people to stop complying and take action.

The game also explores the tension between humanisation and dehumanisation of individuals: the entrants are first seen as anonymous black silhouettes devoid of distinguishing features, and the inspector is under constant pressure to think of them merely as items to be processed. However, it’s harder to think of them in such terms when they stand in front of the inspector’s desk and are seen face-to-face, particularly as so many are humanised by unique details and special dialogue, which is as often funny as it is emotive. Again and again, the inspector is confronted with the humanity of the people he must process, and that humanity is revealed by the silly as well as the poignant.

Papers, Please is not only a clever game, but a game with a heart, and that human factor, more than anything else, might explain its continuing success.

There is no actual recorded dialogue in the game, only distorted vocalisations without intelligible words, which play alongside written dialogue and are often terse and repetitive, given the nature of the job. This surely saved heaps of time and money in terms of development, but also serves a narrative purpose: because the characters do not speak with recognisable accents, the messaging remains broad and universal, albeit conveyed via a Soviet-style setting.

Still one of the best musical overtures in gaming tbqh.

(brand new sentence?)

Whose name is almost certainly a reference to George Costanza from Seinfeld.

i.e. synchronisation between gameplay and story.

Thanks, I think I do own Roadwarden, might try it soon!

Terrific review. Papers, Please was a brilliant work of game design and of fiction in general, and I think it's fair to say that it resonates even harder now than it did in 2013. It's so thoughtfully and beautifully constructed — not a word of dialogue or a pixel of spritework is wasted. Probably Top 5 of All Time in my book.

I think you're totally right to attribute its continued success to its heart and its humanity. No other game does as good a job at representing Orwellian bureaucracy without detouring into overtly political messaging, and I wish more developers would follow Pope's lead in that regard. It's a shining example of how game design can broaden perspectives and even alter worldviews, and that's precisely what we need to be doing in order to prevent actual Orwellian totalitarianism. Not many people will enthusiastically read and internalize Solzhenitsyn these days, but just about anyone can pick up and play Papers, Please.