Remember When Dragon Age Was Good? - Part 2

DA2: Fantasy controversy and crazy virtual friends

In Part 1, I discussed Dragon Age: Origins, with the aim of establishing what the Dragon Age games are actually about. I identified the following themes as essential to the series’ identity:

Injustice in society.

Social conflict along lines of race, class, etc.

Morally ambiguous heroes and villains.

Fantasy scenarios as a means of exploring human conflicts.

A world which feels big, ancient and mysterious.

In the following post, I continue my breakdown of the series with a discussion of Origins’ sequel, Dragon Age 2.

Introduction

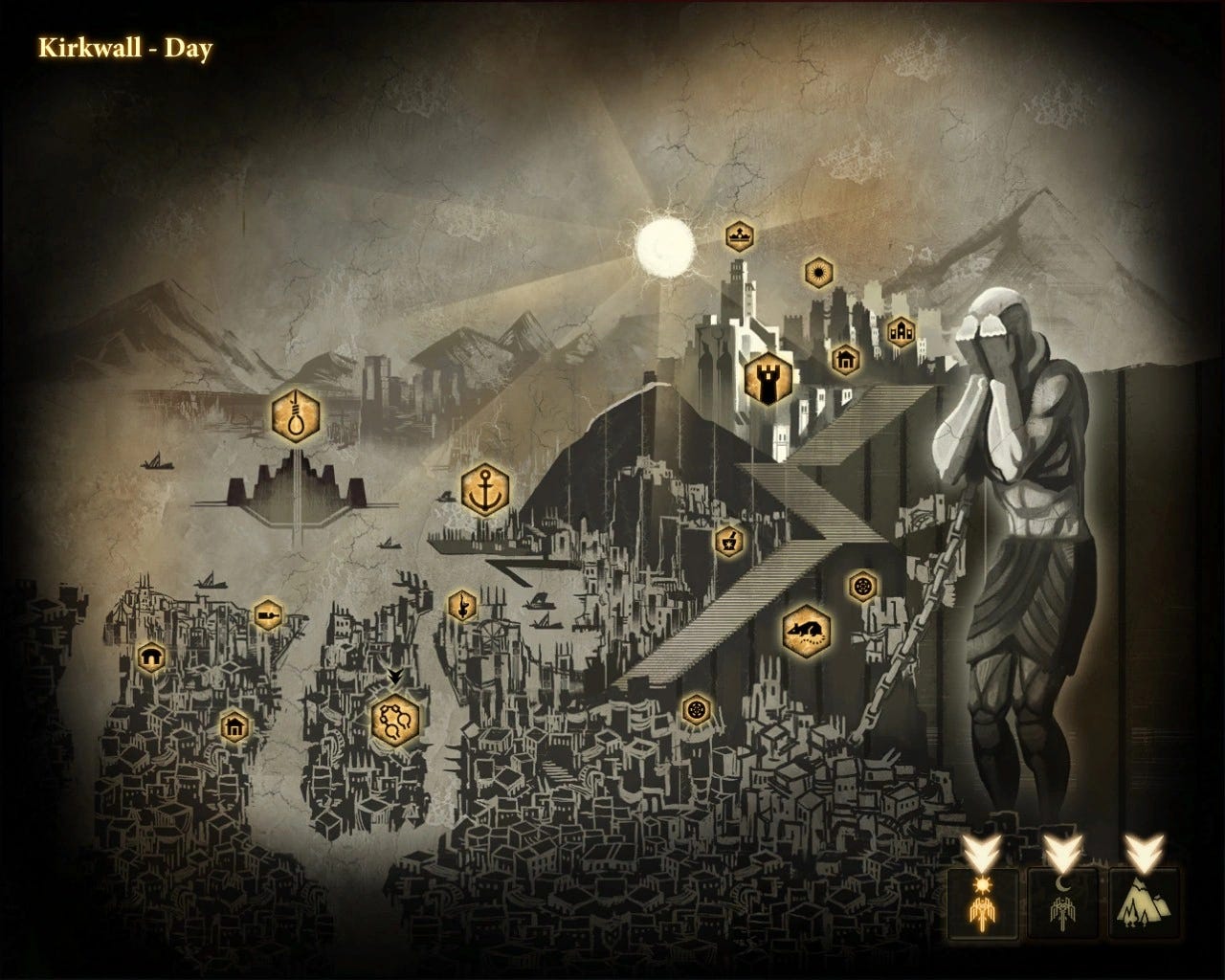

Most fans consider Dragon Age 2 to be inferior to Origins – it’s certainly a lot less ambitious in scope, and has its shortcomings in terms of presentation. The game was rushed out after only 18 months of development, so the end result is far from polished. DA2 has about three dungeon layouts which are recycled ad nauseum, enemy variety is poor1, and you will see waves of those enemies spawn out of thin air during the regularly scheduled ambushes whenever Hawke has errands to run after dark. On the other hand, the art direction is excellent, particularly the stylish UIs, in-game maps and gorgeous narrative cutscenes, which resemble animated murals. Inon Zur also stayed on as the IP’s composer, giving the game a dark and very distinctive soundscape.

Sadly, DA2 has somewhat less roleplaying potential than its predecessor2, thanks to the scrapping of the outstanding ‘origin’ mechanic and the decision to use a voiced protagonist, Hawke, whose backstory, race and relationships prior to the game’s beginning are all predetermined. This was surely an attempt to co-opt the success of DA’s sister series, Mass Effect, which had used this formula very successfully with Commander Shepard, who was also a more ‘fixed’ voiced protagonist and very well-received. As such, the player’s ability to define their character is greatly limited, and I never felt much of a personal connection with my Hawke. He was a pretty cool guy, and the game offered many great opportunities to characterise him through decisions and interactions3, but he wasn’t my guy.

On the more positive side, it’s still very recognisably a Dragon Age game. The focus on social conflicts is more than intact, and this is illustrated beautifully by the player’s companions, a bunch of maladjusted oddballs who are opinionated, divisive, and frequently ‘problematic’, whether it’s Fenris’ single-minded hatred for all mages, Merrill’s breathtaking arrogance, or Anders’ entire personality, which made me want to stab him, but makes others want to sleep with him.

And the great thing about this? The game lets you do either (that is, stab Anders or sleep with him), or both! That’s a roleplaying game.

The brilliant insanity of Hawke’s companions

DA2’s companions also fight among themselves like rabid dogs, and are never afraid to speak their minds – sometimes, as you’re out and about in Kirkwall, you will hear your friends (or associates, at any rate) have arguments that leave your ears ringing. These clashes of ideals and personality aren’t limited to banter, either: on one occasion, the self-proclaimed champion of freedom Anders urges Hawke to sell ex-slave Fenris back to his former master, in a move that is as vile as it is hypocritical. Elsewhere, Fenris will ruthlessly berate Merrill for getting her clan killed; this ‘I told you so’ seems rather redundant in the circumstances. I don’t know what’s more astonishing, that these people behave like this, or that they continue to work together.

However, in light of Veilguard’s excruciatingly boring companions, DA2’s coterie of broken maniacs all look like masterpieces in their own unique ways, and they are infinitely more true to the spirit of Dragon Age. Moreover, their behaviour, while sometimes unhinged, feels more than justified in the context of each character’s background. For example, Fenris’ antipathy to the blood mage Merrill stems from his history as a slave to a cruel blood mage, and his outburst after the incident with her clan seems to relate to the fact that Merrill had everything Fenris lacked (family, community, purpose) and threw it all away.

DA2 also has a pretty strong system for progressing the relationships between the PC and their companions, which differs somewhat from its predecessor. Origins has a fairly typical approval system - companions become more friendly and co-operative with high approval, and more confrontational with low approval, and may eventually become angry and leave the party if approval falls too low. Instead of gaining or losing approval, however, DA2’s companions gain either friendship or ‘rivalry’ points with Hawke.

This system definitely comes with some advantages - it meant that having an unfriendly relationship with a companion does not necessarily mean losing that character and missing out on interesting and entertaining interactions. Rather, it meant that you will see a different side to that character, and see your relationship advance and develop in a different way.

After all, the term ‘rival’ implies a certain amount of mutual respect, and as such a high rivalry score actually has a similar effect to a high friendship score - you will have an easier time convincing a rival at key moments in the game’s story than you will a companion who is indifferent to you. This can mean the difference between life and death, as it may mean convincing a character to side with you in the game’s dramatic final chapter, when you would otherwise have no choice but to fight and kill that character.

Another interesting characteristic of DA2’s storytelling, which is unusual in the RPG genre, is its long timeline. The game takes place over several years, following Hawke’s progress in the city of Kirkwall. Hawke begins as an impoverished refugee displaced during the events of Origins, becoming a prosperous adventurer, and eventually a hero of the city. This also gives relationships between companions time to grow: we see Hawke’s friends (and foes) develop over years rather than months, and also see the political conflict gradually build to boiling point in a way that feels organic and believable, rather than happening overnight.

The Mage-Templar controversy

DA2’s main source of conflict, both within the party and just in general, is the situation with mages in Kirkwall, where the story takes place. Kirkwall’s Circle4 is more brutal than most, with the Templars5 punishing and abusing the mages in their care arbitrarily. The city is also rife with genuine cases of mages abusing their powers. Kirkwall is, by the way, quite literally cursed, due to a long history of blood magic and slavery going back to ancient times, and as a result mages in the city are especially prone to corruption and demonic possession6. All of these factors escalate the Mage-Templar conflict that has been brewing for generations, and the player is ultimately forced to choose a side.

For over a decade, fans have passionately argued about the questions DA2 poses about mages, and whether Circles need to be abolished or reformed. There is no easy answer to this conundrum – within the setting, the most prominent society in which mages are free is the Tevinter Imperium, a cruel empire ruled by elite mage families7, in which much of the population is enslaved and slaves are abused, experimented on or even sacrificed by their mage masters in blood magic rituals8. That being the case, we have to wonder what would stop mages from banding together to tyrannise other countries, as they did in Tevinter, if not for the Circles. On the other hand, we see abundant evidence that Templars often abuse the mages they are in charge of, and that many succumb to possession or resort to blood magic as a direct result of this abuse. As such, it does kind of look like the current system is a) cruel and b) unsustainable.

The fact that players have been discussing this problem so heatedly for so long, and tend to have strong feelings one way or the other, is a testament to the writers’ skill in presenting fantasy dilemmas in a realistic way that engages a grown-up audience and makes us care, without necessarily preaching to us or telling us what to think. When you play old Dragon Age games, you never feel that you are being talked down to by the writers or treated like a child who has to be taught right from wrong. Instead, you are presented with complicated dilemmas, and required to make a choice, and you might never know whether you did the right thing or not9.

The antivillains of Kirkwall

In DA2, the series’ affinity for antivillains and morally complex characters is also more than intact, notably with Meredith, who champions the Templar cause, and Orsino, who represents the Mages. These characters are compelling because they are both so fundamentally inflexible - each believes wholeheartedly that they are in the right, and both are ultimately willing to go to horrifying extremes to achieve their goals10. They are also both immensely hypocritical, and yet neither is ever depicted as sadistic or ‘evil for the sake of evil.’ Orsino has good reason to despair about the future of the mages he is responsible for, and to feel that he has no choice but to resort to forbidden magic to save them. Meredith, likewise, has good reason to see magic as inherently dangerous11. Hawke sees endless evidence of this in Kirkwall, and in fact is personally affected by dark magic in a highly traumatic way12.

Another excellent antivillain in DA2 is the Arishok, the chief of a group of Qunari soldiers stranded in Kirkwall. The Qunari13 are a race of grey-skinned giants with dragon-like horns, and their society is centred around their religion, the Qun, and ordered into strict castes. The Arishok is a commanding presence, radiating power and conviction, and his disgust with the decadent state of Kirkwall is palpable. His dynamic with Hawke is also very compelling, as he recognises Hawke as a fellow warrior and leader, and also as a fellow outsider in Kirkwall. Ultimately, when the two inevitably come to blows, this dynamic of mutual respect adds a certain pathos to the overall drama. As harsh as the Arishok’s methods are, he is in some sense a kindred spirit to Hawke, wishing to set this doomed city right, and his failure foreshadows Hawke’s.

Perhaps the best quality of DA2’s narrative, which is intimately tied to the social nature of its conflict, is the tragic personal story that unfolds. Through each act of the story, Hawke suffers again and again from misfortunes outside their control, and the same thing can be seen in so many other questlines within the world. Fundamentally, it’s a story about loss, about the uncertainty of life, and the hardships we all have to contend with14.

Hawke may be a hero, but is ultimately just a human being, powerless to prevent a series of family tragedies, let alone to stop the conflict that erupts in Kirkwall. Whereas an Origins playthrough typically ends on a triumphant note, DA2 always ends in a more sombre way, with Hawke’s whereabouts unknown, having left Kirkwall in the aftermath of the disaster.

Closing thoughts

Although I would agree with the general consensus that DA2 is weaker than Origins, it remains a very respectable RPG in its own right, and is also very successful as a Dragon Age game. In other words, it is true to the spirit of Origins, continuing to develop the setting and to engage with Origins’ themes and ideas. It is a story about social conflicts, and it respects its audience, presenting us with challenging issues and morally ambiguous characters, who players have responded to in wildly different ways.

The conflicts among Hawke’s companions are not only entertaining and informative, but narratively important, as they give voice to different views on the Mage-Templar conflict at the heart of the story, and as we get to know them we learn about the different life experiences that inform each character’s point of view. It is a sound political story, in which the hero ultimately fails to prevent disaster (as would-be heroes often do in real life), and the hardships suffered by Hawke and others throughout the story add great pathos to the game.

To be continued…

I hope you like giant spiders!!

At least according to my own criteria.

Suffice to say my Hawke did not suffer fools gladly.

The institution where mages are confined.

Religious warriors and de facto jailers of the mages.

Tl;dr, all of that blood sacrifice in ancient times weakened the walls between reality and the Fade, the realm of spirits, demons and magic. This makes it much easier for mages to tap into dark forces, and also makes it easier for demons to slip into the material world, whether physically or by possessing a victim.

(magic is very hereditary in Thedas)

Kirkwall used to be a Tevinter colony, hence its dark history.

i.e. the Geralt of Rivia experience.

On the surface, Orsino seems like a responsible well-meaning guy, and Meredith seems like an unhinged zealot, but oh boy, suffice to say that Orsino has something very dark going on behind the scenes, which is only revealed in one variation of the game’s final act.

In the World of Thedas book, Meredith’s backstory is explored - as a child, her sister was a mage who became possessed by a demon, and killed more than seventy (!!!) people. The traumatised Meredith was saved by a Templar. This background isn’t necessary to understand Meredith’s character, but it does add to it, and illustrates very clearly that the mage issue is not black and white, and that Meredith is more than just a screaming zealot, although she is also that.

If you know, you know.

Introduced magnificently in Origins by the character of Sten, a Qunari soldier and (optional) companion of the Warden. Sten is characterised by his laconic yet witty speech, and by his inflexible and often alien moral code, and may ultimately become a devoted friend to the player.

One reader noted the similarity between Origins and The Witcher, and DA2 is also very Witcher-like in this regard.

DA2 was such a good game. I remember being obsessed with Flemeth and her "reckoning" I will never understand how veilgaurd just gave up that plot point