More on horror can be found here.

Introduction

Recently, I watched Psycho for the first time. It seemed like the sort of thing I ought to do, since horror is at least nominally part of this newsletter’s mandate, and Psycho is a work of horror so foundational that basically everyone knows basically everything about it, even those who haven’t seen it.1 As such, not having seen it was beginning to feel like a gap in my education, and happily, it has now been addressed.

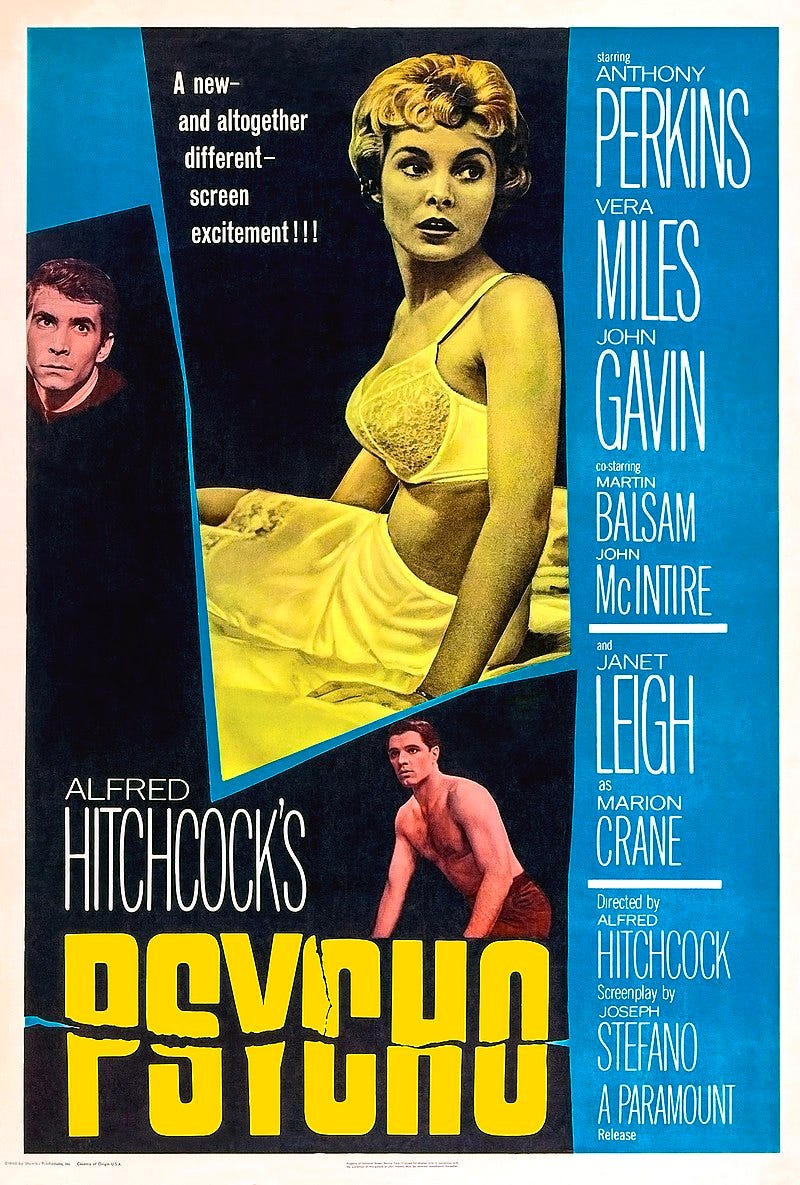

This is not to be a review as such: Pyscho is so well-known that it would be fairly redundant to weigh and rate it, and critique would be presumptuous even for me. I will, however, say here at the top that the movie is really, really good, and as watchable today as it was in 1960. The direction is immaculate, the casting serendipitous, and the gradual build of tension second to none. It’s quite possible that Hitchcock peaked here, and that’s saying a lot, given his record.2

This is not to be a comprehensive thematic analysis either. Again, it would be basically redundant, since we all kind of know through osmosis what Psycho is about, i.e. a murderer with a split personality, his other half being his abusive mother. There’s a definite incestuous vibe,3 a more-than-recommended-by-doctors dose of Freud, and, in case anyone didn’t get it, a psychiatrist explains it all at the end in the manner of Hercule Poirot.4

(As a side-note, there’s a question as to whether Psycho is transphobic: Norman famously cross-dresses as Norma, and The Silence of the Lambs would also prominently feature a trans-adjacent serial killer. This won’t be today’s focus, but it does seem like a query worth pursuing, given that certain mainstream newspapers have just straight-up lied that a high-profile killer was trans, which unsurprisingly turned out not to be the case.)

What I want to focus on here is the part of Psycho that hasn’t made it into the popular consciousness, i.e. the part that you actually have to have seen the film to know about. What was most surprising to me, knowing Psycho only by reputation, was the extent to which Marion Crane, the first victim (played by Janet Leigh), is characterised and developed.

Most people, if they know who Marion is at all, only know about the shower murder scene, and, if this was a typical horror flick, there would indeed be nothing more to Marion than the shower scene. But as we’ll see, that scene is nothing in isolation: it is so shocking and so impactful because it is the culmination of almost an hour of setup, which is absolutely integral to the film, and crucially distinguishes it from exploitation. Whereas exploitation is built merely on gore and tits, the horror of Psycho is built on a far stronger foundation: it is built on empathy.

Meeting Marion

We first meet Marion in a hotel room after a tryst with her boyfriend Samuel, who is handsome but broke, saddled with his father’s debts and with alimony to his ex-wife. They talk about a future together, but the hope is frustrated by money, or lack of money, and therefore poverty is an overshadowing theme throughout the film.5

Accordingly, the next scene shows Marion at the office where she works. Here she encounters Cassidy, a businessman who is in talks with her boss. Cassidy is a really nasty figure, a wealthy older man who immediately gets into Marion’s space and proceeds to ‘flirt with’ (read: sexually harass) her in a very blunt and pushy way, and persists even though Marion signals her disinterest clearly and firmly. He boasts about his money, and the insinuation is that he’s willing to trade money for sex, and is broadcasting that as loudly as possible. He’s apparently looking to buy a (very expensive) house for his eighteen year old daughter, and this allusion underscores how inappropriate his interest in Marion is - he’s likely married, and she’s likely not much older than his daughter.

The framing, with Marion (played by the very slight and delicate Janet Leigh) sitting while Cassidy perches on the edge of the desk and leers over her, emphasises his power and her smallness, and the viewer can feel her discomfort and indignation, which is further informed by our knowledge of the poverty that limits her, while this toad of a man so crudely flaunts his wealth. The scene’s unpleasantness is compounded by Marion’s isolation: her married female co-worker is clearly oblivious to her discomfort, saying that Cassidy was merely ‘flirting’ with her, and her boss keeps his mouth shut.

The upshot of the scene is that Marion is entrusted with 40,000 dollars in cash, which she is supposed to deliver to the bank. In modern money, this is the equivalent to nearly half a million dollars: it’s a really enormous sum to entrust to a minimum wage worker you’ve just harassed, but Cassidy is nothing if not oblivious.

So, Marion does what any malcontent proletariat would do: she takes the money home, thinks for a bit, then promptly gets in the car and runs away with it. The scheme is pure impulse, and obviously half-baked, such that she doesn’t include Sam in the plan, though all signs are that she really did want to marry him. Sheer spite against Cassidy is evidently a motive: she smiles in the car while voiceovers play of Cassidy and her boss reacting to the theft. Cassidy indignantly says at this point that ‘she was flirting with me:’ the distortion reveals the cleverness and awareness of the screenwriter, who at every moment is encouraging the viewer to identify with and root for Marion and her audacious act of rebellion.

Unfortunately, Marion’s trouble with men does not end with Cassidy. She is stopped and questioned by a police officer, who follows her, his suspicions roused by her increasingly anxious behaviour. Again, the direction emphasises Marion’s vulnerability and her femaleness through the small stature of the actress as she sits in the car and the imposing male officer, expressionless and incrutable behind dark glasses, gets in her space by leaning close to the window.

The scene takes place on a deserted highway, with no witnesses, and although the officer does her no harm, there’s a sense of threat, especially in light of the earlier scene with Cassidy. The cop has power, and Marion does not.

Meeting Norman

Following this, Marion manages to lose the cop, and arrives at the Bates Motel. Here, things start to get more familiar, thanks to the film’s massive pop culture footprint. She is greeted by the shy and awkward Norman, who invites her to the house for dinner. Marion agrees somewhat reluctantly, only to overhear a row between Norman and the unseen abusive mother (actually also Norman), who jealously forbids him from bringing Marion to the house.

They instead eat in the motel’s parlour, where Norman talks about his ominous hobby of taxidermy,6 his ‘sick’ mother, and his own spiralling mental health. He believes that everyone is caught in their own ‘trap’ which they cannot escape, and it’s clear that Marion can relate: as they talk, she seems to come to the decision to return the money and own up, knowing that she won’t be able to get away with it. The conversation takes a darker turn when Marion delicately suggests that Norman should put his mother in an institution, and from his furious tirade, it becomes very clear that Norman himself must have been confined at some point. This scene builds tension masterfully as Marion slowly realises that something is seriously wrong with her host, but she is finally able to extricate herself.

Again, there’s a definite sense of sexual menace to the scenario, and again, Marion appears very vulnerable next to the tall and lean Norman. The morbid isolation of both the motel and its owner heightens the sense of danger, which only increases when he spies on her through a peephole as she gets ready to shower. The horror of the ensuing attack is inseparable from this sexual threat, as there’s an ambiguity to the approaching figure behind the curtain’s intentions: is it Norman or Norma, and are they intent on murder or rape? It need hardly be stated that the repeated stabbing of the knife is symbolic of Norman’s sexual frustration.7

The murder scene was boundary pushing at the time, due to both the nudity (which is more suggested than actually shown) and the subtext, yet what we actually see is tame by the standards of 21st century entertainment. However, the horror is still very acute, because through the film’s gripping introduction, the viewer has come to care about Marion’s fate, and to feel protective towards her. We empathise with Marion because of her frustrations over money; because we see her harassed at work; because her theft of the money is brave, if ultimately foolish. For that first forty-eight minutes, she really is the film’s heroine.

Because the viewer is invested in Marion’s fate, the scene of the murder’s aftermath is particularly powerful: here, we see Norman ‘discover’ Marion dead (the murder having been committed by the Norma persona), and proceed to clear up, carefully scrubbing the blood from the tiles, and piling Marion’s body and possessions in the back of her car, which he disposes of in the nearby swamp. The scene is particularly unsettling, because there is a definite sense that Norman has done all of this before (which is later confirmed), and every step of the careful clean-up is shown, taking almost ten minutes of the film’s run time.

The director’s characteristically ‘voyeuristic’ camera work, which gives the earlier scenes a sense of intimacy8 that increases the viewer’s identification with Marion, here makes the viewer feel like a witness or even an accomplice to Norman. There is a systematic, mundane quality to the disposal of this human being that we have come to care about, and at this point, the viewer is hooked: we have to see the killer brought to justice, and so it is maddening when, during the clean-up, we see Norman find and dispose of the newspaper in which Marion hid the money. Had it been left behind, it might have confirmed that she was at the motel.

All of this, to my mind, is what elevates Psycho so far above typical horror films. Generally, victims in horror exist on a spectrum ranging from monster fodder to unlikeable bastards who make us vicariously identify with the killers. Psycho, however, works on a different principle. It works because its first victim is so carefully humanised over nearly an hour. Marion plays on the viewer’s sympathies as an underdog and an everywoman whose struggles we can identify with, and whose life (and role as heroine) is abruptly cut short. Through the remainder of the film, we are glued to the screen, because we want justice for Marion, and so we root for the ill-fated PI Arbogast, and later for Sam and Lila, Marion’s sister, as they investigate and ultimately expose the killer.

Closing thoughts

Viewing Psycho is an interesting experience, in that what is arguably the most vital element of the film, the make-or-break ingredient, is far lesser known in pop culture than the scares, cross-dressing, and psychoanalysis of the movie’s second half. Had the Marion story - from tryst, to harassment, to the grimly methodical disposal of her corpse - been compressed by even a minute, the film’s impact would have been greatly diluted, and perhaps it would not have been such a phenomenon.

It also seems to me that Psycho’s first half might be due a re-assessment by feminist academics, who have historically been more interested in the Norma/Norman relationship, with Norma cited by Barbara Creed as typifying the ‘castrating mother’ monstrous-feminine archetype. However, Marion’s story is also deserving of attention, and is in a sense ahead of its time.9 Both male and female viewers are led to empathise with Marion’s plight; to see Cassidy’s ‘flirting’ for the inappropriate pestering that it is; and to share Marion’s subsequent unease in the presence of imposing men such as the policeman and Bates himself. Thus, we are confronted with the fears, frustrations and dangers that women have to contend with in the real world.

The film’s underlying concern with money and power is inseparably connected to this, in that Cassidy’s wealth and status enables his behaviour; his money is what allows him to ignore Marion’s boundaries, and prevents her from snapping at him, however much she might want to. The film is far from didactic, yet all the more effective for it. You don’t need to be steeped in intersectional theory to get that Cassidy’s pestering and Norman’s violence are part of the same spectrum, as the film illustrates that point so clearly and vividly. Psycho uses empathy as a tool to generate horror, but in the process it also ends up doing something more sophisticated, and that deserves recognition.

Especially those who haven’t seen it!

Not an endorsement of his personality, which was abominable. The surprisingly sensitive portrait of Marion in Psycho can most likely be attributed to the screenwriter Joseph Stefano and/or to Robert Bloch’s novel, rather than Hitchcock, who is generally (and accurately) regarded as a giant misogynist.

It’s a sad and somewhat spooky fact that Anthony Perkins, who played Norman, was sexually molested by his mother, and his life story was uncannily similar to Norman’s, .

To be fair, we’ve all been marinating in Freud for sixty-five additional years by now: this stuff was still relatively new in 1960, and required some explanation.

It’s also clearly a factor in Norman’s isolation and decline; the new highway has made his motel almost obsolete, and with no guests and no future, he’s deprived of stability, routine, and human company. He’s alone with ‘Norma.’

Connected to a) the preserved corpse of Norma, and b) the tendency of real serial killers to harm animals and to keep trophies from victims.

I’m not convinced Norman’s name isn’t a masturbation pun. People address him simply as ‘Bates’, because ‘Mr Bates’ would be a bit too on the nose.

Unwanted intimacy, in the case of Cassidy’s intrusion at the office.

Again, probably attributable to Bloch/Stefano rather than Hitchcock.