More on video games can be found here and here.

Introduction

For some time now, I have been immersed in a world of apocalyptic warfare, mass delusions, political repression, and the looming spectre of nuclear annihilation. But I’ve also been playing HighFleet, a ‘dieselpunk post-apocalyptic strategy action-adventure game’ released in 2021, which had been sitting untouched in my Steam library for some time. As dense as its genre labels are, they don’t really even begin to do justice to it, and are more useful to taxonomists than to we who resort to the humanities to explain our relationships with video games.

HighFleet is a really amazing game, that grabbed me in a way that few games do. In many ways, it feels tailor-made for me: it’s post-apocalyptic, and it’s highly original, while at the same time drawing inspiration from sources which are dear to my heart, namely Dune and Lawrence of Arabia, both of which were cited as influences by the lead developer. As such, it could be classified as Orientalist, in that its setting is heavily based on Central Asia and the Middle East as seen through European eyes. This, as the great Edward Said discussed in granular detail, tends to come with a lot of baggage.1

However, I am going to be making the case that HighFleet engages with this material in a fairly nuanced way, not least by putting the player in the shoes of a Tsarist prince who is not necessarily the hero of the story, and may or may not be the Antichrist. To this end, and through various ludonarrative devices, the player is not only encouraged but pushed to be a ruthless, lying bastard while posing as a saviour. If I had to condense my response to HighFleet to a single soundbite, I would say that the game strongly advances the idea that there’s no nice way of waging a colonial war, a message that is particularly resonant in the context of a military adventure in the Middle East.

On that front, there’s a lot to unpack; in Part 2, we’ll be getting into the Soviet-Afghan War, which was cited as a key influence by Konstantin Koshutin, the lead developer,2 as well as the various design features that propel the player along a villain arc, and the game’s relationship with Orientalism. But first, it’s sensible to begin with an outline of the story’s premise, art design, and an overview of the mechanics, which are ultimately brilliant, but admittedly opaque and under-explained.

Outline

HighFleet is set on the world of Elaat, a barren feudal planet ravaged by war. In this setting, wars are fought mainly by giant metal airships powered by thousands of tons of methane gas.3 The two fictional nations featured are the mostly-Slavic Romani, who seem to rule much of the known world, and the mostly-Muslim Elaim, who live in the subjugated Kingdom of Gerat.4

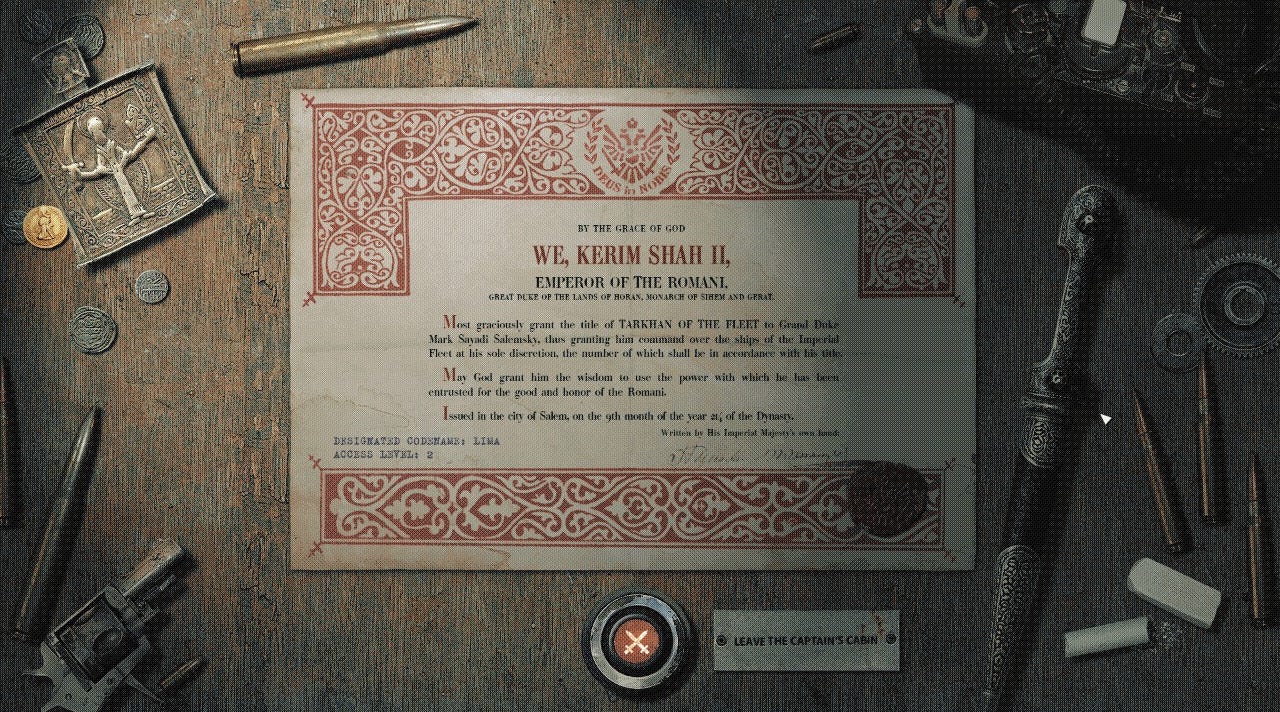

The game’s story revolves around an uprising by the Elaim Gathering of Great Houses,5 under the leadership of a rebel Romani governor who deposed the puppet King Ali and declared a Republic in Gerat. The war has been raging for seven years at the start of the game, at which point the Romani Emperor’s son, the Duke Sayadi,6 (controlled by the player) is dispatched on a mission to take the rebel capital of Khiva.7

In this mission, he is initially joined by Pyotr Ignatovich Shahin, his devoted mentor and friend,8 as well as the chillier Admiral Daud, and by the Elaim Prince Fazil, son of the deposed King Ali.

The plot thickens with a rebel nuclear attack on the Romani capital, leaving Sayadi’s strike force stranded in enemy territory with no choice but to push on through hostile country, fighting a guerilla war against a vastly more powerful enemy. The player must contend with countless enemy garrisons, as well as mobile fleets that will move to investigate any alarm. Morale has to be kept up, time and money must be carefully managed, and above all, the player has to reckon with the grinding attrition of constant fighting.

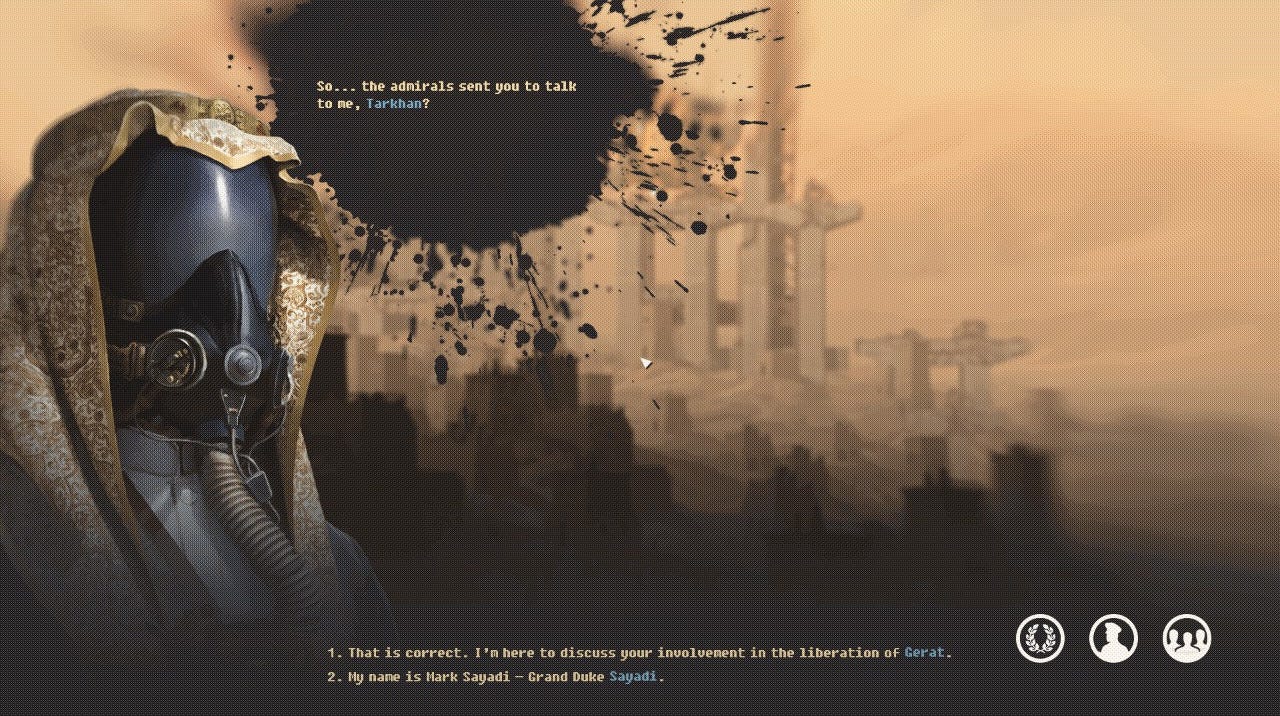

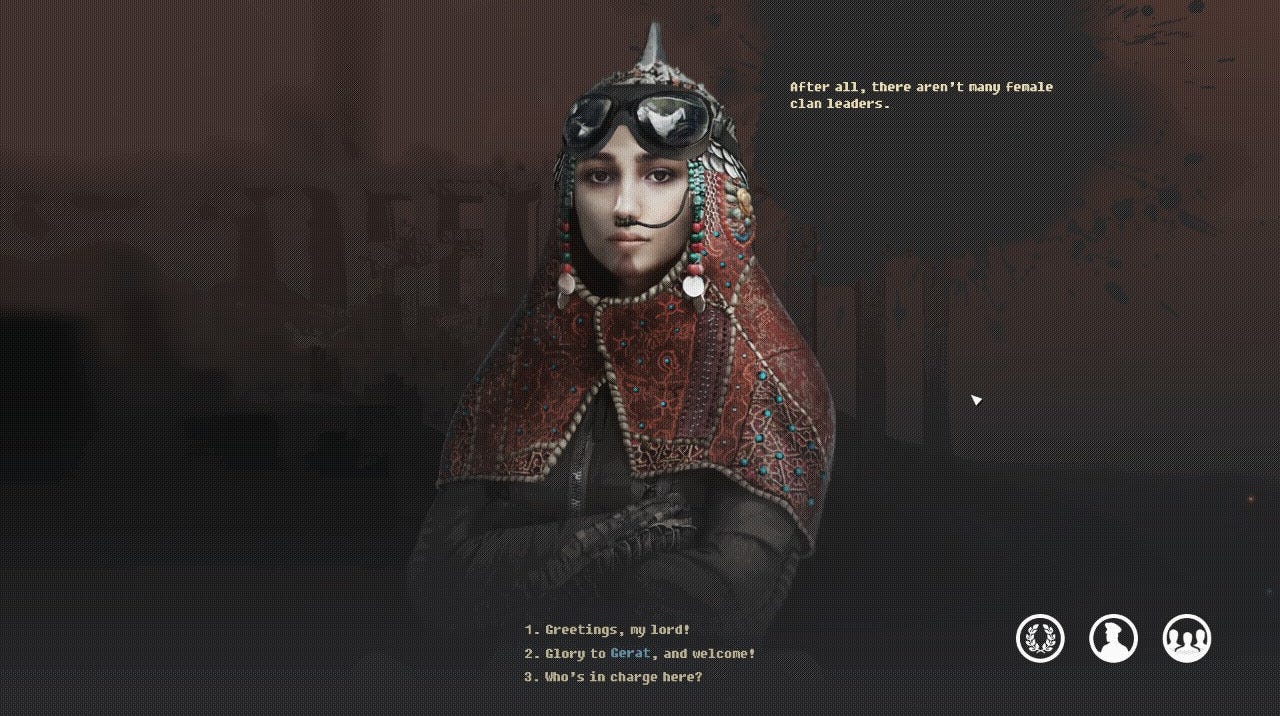

But the odds aren’t entirely against Duke Sayadi. There are many potential allies to be found in the form of Tarkhans, nomadic military leaders outlawed by the Khiva regime. These Tarkhans are a motley crew of Elaims and Romanis, ranging from disgruntled former rebels, to stranded Imperial holdouts, to unpretentious sky-pirates.

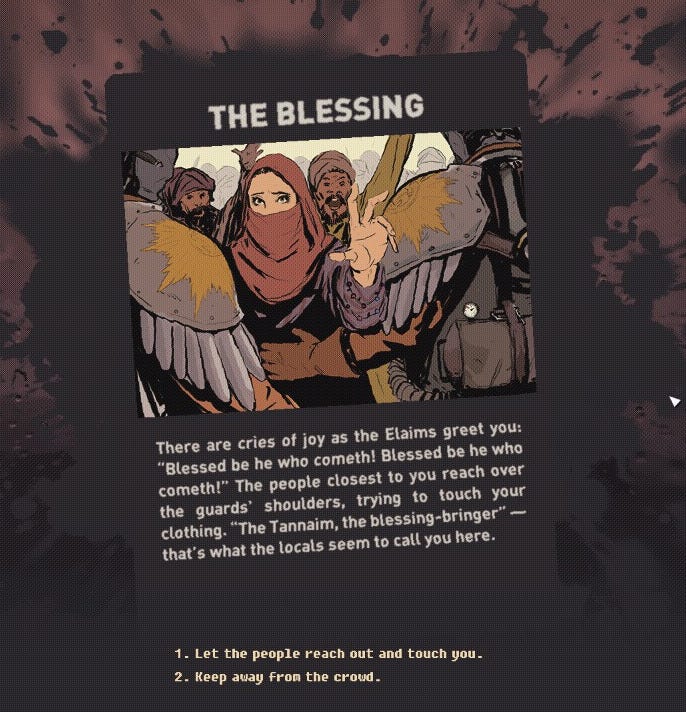

Moreover, the people of many Gerati cities are dissatisfied with the governor’s rule, and Sayadi, as one of the few aristocrats capable of reading certain ancient scriptures,9 is in a position to cynically leverage the people’s religious beliefs to his advantage, presenting himself as a prophet and a saviour.

Presentation and mechanics

It has to be said, in no uncertain terms, that HighFleet is an absolutely gorgeous game, radiating retro military style. The game can roughly be considered to have two ‘layers,’ one strategic, the other tactical. The former presents the player with a bleary digital map of Gerat crowded with a host of worn buttons, switches, knobs, levers, radio equipment, radar displays, and infra-red sensory gear. The game’s manual is very much worth a look for a sense of HighFleet’s visual flair, and also clarifies a few story details that aren’t directly addressed in the game.

The game is complex and fairly deep in terms of the variety of strategies at your disposal - for example, you can send out bombers and fighter planes from aircraft carriers, launch cruise missiles to attack enemy fleets at long range, intercept radio messages from enemy airships, and detect radar signals via special sensors. The trouble is that this complexity is a double-edged sword, in that it is a) initially overwhelming due to the sheer volume of incoming information,10 and b) all strategies are not created equally, and it must be said that HighFleet does not always give the player the best advice.

For example, the game’s introductory section spends a lot of time teaching you to use the radio to intercept signals, but no time whatsoever teaching you to launch ballistic missiles. You would think, therefore, that radio messages must be more useful than missiles: nothing could be further from the truth. Clearly, HighFleet wants you to embrace guerilla warfare and put information-gathering first, yet in actual fact the player is going to end up fighting enemy fleets sooner or later, and ought to know how to do that. The mobile enemy fleets (called strike groups) are finite in number, and traversing Gerat becomes far less daunting once a few have been knocked out. Moreover, you can quite feasibly complete a whole playthrough without bothering to engage with the radio interception system. Strictly speaking, it’s much, much more useful to know how to deploy bombers and missiles, yet if you want to do that, you might just end up consulting the manual.

Similarly, there are certain elements of your interface that are not only of minimal use, but actually counter-productive. The community (rightly) urges struggling players to practice strict ‘radar discipline,’ i.e. to avoid using radar at all costs, because radar signals can be detected by the enemy over a huge distance, and used to pinpoint the player’s location, which in many situations means game over. Notionally, radar and radio intercepts are useful for locating enemy transport ships, which can be captured and sold for money, but in actual practice, a) you’re going to run into transport ships by chance often enough anyway, and b) you are generally going to have overriding strategic concerns, like not being detected and losing half your fleet to seeker missiles. It’s entirely possible to beat HighFleet without ever turning your radar on, and in fact it’s not only possible but preferred.

Of course, once you start to get a sense of what’s worth investing in and what’s set dressing, the strategic elements of HighFleet are more than serviceable. It’s an absorbing, gritty military adventure, in which the player has to grapple with the problems that generals have faced throughout history: How can I best obtain the supplies I need? Do I allow the troops to rest, or keep pushing forwards at the cost of morale? Should I sacrifice a few men now, or more men later? Is it better to fight or to flee? Is this reward worth the risk? All of these problems are presented superbly in HighFleet, along with the associated political and moral quandaries, which we’ll get to in Part 2.

HighFleet’s strategic layer is joined by a ‘tactical’ layer, which puts the player in direct control of airships engaged in dogfights with enemy craft. These battles are a huge selling point for the game, and are both visually stunning and absolutely gripping to play. Again, there’s a lot of depth in terms of the various available fighting ships, all of which are highly customisable, and can even be built from scratch if you’re technically-minded.11 Ships can be fitted with armour plating, with additional engines, with missiles, with flares, and any weapons can be swapped or moved around at your discretion. Every individual part of a ship is destructible, so that you will often see ships bursting into flames when their fuel tanks or ammunition stores are struck, though ships can continue to limp on even after losing engine pods and landing gear. The visual effects are incredible, and have to be seen to be fully appreciated.

HighFleet’s battles are defined by flickering digital displays, brilliant flames, and trails of scalding vapour from jet engines. As ships tumble between clouds of hissing rockets and phosphorescent tracers, the screen darkens and heavy breathing can be heard as pilots struggle to remain conscious under crushing G-force. All of this is, of course, accompanied by the hardest hurdy-gurdy tracks this side of The Witcher 3,12 and the sound design is as impressive as the visual effects.

It’s a mesmerising depiction of warfare in the age of industry, at once exaggerrated and disconcertingly real. The game’s art style plays to this sense of hyper-reality: for all their preposterous bulk, the drab, boxy and utilitarian look of HighFleet’s ships draws much from real military aesthetics, helping to ground these mechanical leviathans in reality. Unnervingly, many of these battles take place directly above inhabited cities, which will be deluged with stray shells, rockets and burning wreckage. We can only imagine the human cost of Duke Sayadi’s campaign, and the emphasis on the battles themselves creates an emotional distance between the player and the unseen collateral, whose fates are presumably of little interest to the Duke.

HighFleet’s realistic design philosophy can also be seen in the in-game art, which is stellar, particularly the character portraits, which draw many recognisable elements from the real world. In HighFleet, we can see clothing and accessories identifiable with real cultures, real gas masks and uniforms, and sometimes even familiar faces of historical figures, which are eclectically combined to produce unique and striking portraits.

HighFleet is not replete with mini-games, although the process of manually landing ships, which facilitates faster repair, falls into this category. Given the titanic bulk of even the smaller airships, this is a very delicate and often fraught process, particularly with heavier ships, which are liable to snap a landing gear and go up in flames if you misjudge. Landing damaged ships is even more perilous, although happily the game does allow you to retry or cancel a doomed landing, as well as restarting battles at any time. With cloud condensation on the screen, jets of gas and flame reacting with surfaces, and bright digital displays, even a smooth landing is always a great spectacle.

Finally, there is the nuclear war mechanic, which is remarkable in that a) almost everyone in this setting has nuclear weapons, including a pirate who brings a ship with not one, not two, but SIX nuclear missiles to your fleet, and b) you can start a nuclear war at any time, but you’d damn well better be sure you’re in a position to finish it. Using nuclear weapons isn’t recommended per se, because the enemy has a lot more missile carriers than you do, and even if you survive a nuclear attack, you’re going to be grounded for days dealing with repairs, and you’re never going to financially recover from it.

Nuclear attacks in HighFleet look incredible, featuring the biggest and most beautifully rendered explosions in gaming (at least in this price range), and even if intercepted, the splash damage is going to set your whole fleet on fire and hurl thousand ton cruisers across the screen like toys. If this happens near a city, casualty figures in the hundreds of thousands will pop up. Of course, nuclear war is inevitable in the endgame, since once the Duke’s forces take the capital, there is a role-reversal, with the Duke given command of many new ships and unlimited resources, but required to defend against multiple trigger-happy nuclear-armed fleets. It’s intense, to say the least.

The game is technically supposed to be played as a roguelike, but honestly, I would recommend playing on the easier difficulty first, which offers multiple save slots, allowing you to experiment, learn and see what HighFleet has to offer without being brutally gatekept by the opaque mechanics and merciless rebel forces. If you love to suffer, the higher difficulty modes are always there, but even the ‘easy’ difficulty is challenging enough to keep the common or garden masochist engaged through a first playthrough.

A typical first playthrough is likely to take between twenty and thirty hours, although there are likely to be false starts as campaigns crash and burn, and true to form, the game is nothing if not misleading - it’s heavily implied that you should rush to take the capital as soon as possible, but in fact the penalties for taking your time are very light, and outweighed by the benefits of a careful, thorough war of attrition.

To be continued…

If you can stomach listening to Ben Shapiro for three seconds, you’ll probably get a representative sample of the kind of murderous belligerence that tends to come with Orientalism.

(who is Russian, and therefore familiar with the history, for reasons we’ll get into in Part 2)

With its apocalyptic desert setting, airships, nuclear anxiety, and Central Asian imagery, the game may or may not have a relationship with Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind. Koshutin’s first game, HammerFight, featured airships battling giant insects, much like Nausicaa. Shuna’s Journey, a book Miyazaki made somewhat before Nausicaa, features a city similar to the real-life city of Khiva, a fictional version of which features in HighFleet, and Miyazaki’s earlier People of the Desert also centred on Central Asia and the Silk Road.

The name Gerat is presumably derived from Herat in Afghanistan, where a major uprising took place early in what would become the Soviet-Afghan War.

Dune-esque language: Dune’s Great Houses are interplanetary aristocrats, distinguished from the planet-bound Houses Minor.

Full name Grand Duke Mark Sayadi Salemsky. A name so long it had to go in a footnote, so as not to disrupt the flow of the paragraph.

Named after Khiva in Uzbekistan, which was historically a major centre of commerce on the Silk Road.

Think Gurney Halleck.

Thanks to the Missionaria Protectiva his illustrious family traditions.

Koshutin admitted that, in hindsight, the game’s ‘tutorial’ prologue section really needed to be twice as long as it was.

I’m not particularly, but I’ve found the game’s standard ships perfectly serviceable, with only a few necessary modifications. All ships aren’t created equally, but there’s a wide variety adapted for different roles, and many are worthwhile.

The whole OST is very much worth a listen even if you don’t play the game, the apocalyptic vibes are impeccable.

Definitely an underrated favorite. Took forever to feel like I had anything approaching a handle on it

buying this.