What does Armored Core VI have in common with a Werner Herzog documentary?

On disembodiment, the Gulf War, and Mobile Suit Gundam

More on video games can be found here.

Introduction

People associate From Software’s video games with many things: atmospheric settings, great level design, comically large swords, and of course formidable bosses. What we don’t tend to think of are the documentaries of Werner Herzog, one of the film industry’s most outstanding Weird Guys (who would, to be fair, be a great Dark Souls NPC).

However, Armored Core VI is no ordinary Fromsoft game. Indeed, in terms of gameplay, story, and visual style, it is in many ways a conscious attempt to break away from the formula of the last 15 years or so, and to do something a bit different, and it’s very successful in that task.

For those not familiar, AC6 is heavily inspired by mecha anime, i.e. anime about giant robots and the autists troubled young people who pilot them, and accordingly, it puts the player in the shoes of a mech pilot.

Becoming one with the machine

First of all, and before getting into its Herzogian credentials, it has to be said that AC6 is probably the best mecha game in existence,1 by no small margin: it looks amazing, with fantastic graphics and stylish art direction, drawing heavily on classics of the genre like Gundam and Evangelion. The gameplay is also very, very good. It revolves around thrilling mech battles, demanding skill, intuition, and lightning fast reactions from the player.

Whereas most Fromsoft games are about limiting the player’s mobility through tight stamina pools and restrictive terrain, AC6 offers unprecedented speed and agility, and gigantic environments to fight in: mechs dart across the screen like dancers, dodging and weaving amidst luminous jets and vapour-trails, leaping buildings and skating across lakes. All of the staples of the mecha genre are here, from railguns, to energy swords, to characters with alarming names (such as Middle Flatwell, Thumb Dolmayan, and V.II Snail), and the game’s fluid animations and effects make battles an incredible spectacle.

What is most striking about AC6, though, is the fact that it really makes you feel like a mech pilot. To explain what that means, a few words about the genre are necessary. Mecha tends to centre on epic rivalries between ace pilots, whose original motives become irrelevant in their obsessive struggle for mastery. It also likes to muse on the dichotomy of human and machine, which are brought into harmony as pilots adapt to their mechs, making them extensions of their own bodies, until they no longer feel complete or fully embodied without them.

Accordingly, AC6 is highly skill-based, and unlike an Elden Ring, where it is possible to game the system by optimising your stats and equipment, AC6 offers no shortcut to gitting gud. It’s all about finding a loadout that suits you, and then training and conditioning your reactions until everything becomes second-nature. When you - the player - become one with the machine, suddenly boss-fights that used to be insurmountable become effortless. There’s a nice synchronicity with the narrative here, because of course this is exactly what the unnamed and unseen pilot is also experiencing.

Mecha and war

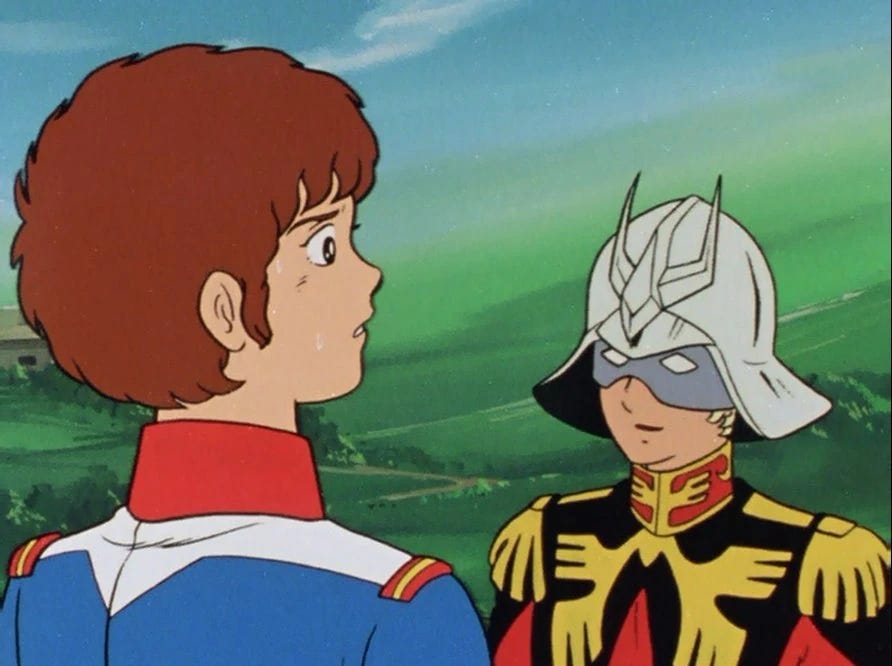

However, for our pilot, this identification with his machine does not come without a cost. Basically every mecha anime since Mobile Suit Gundam in 1979 has been… surprisingly bleak,2 luring viewers in with boyish escapism only to ambush them with gloomy ruminations on the horrors of modern warfare. MSG is essentially a war drama, centred on Amuro Ray, a young boy conscripted into a brutal, nigh-apocalyptic struggle between the Earth Federation and the Principality of Zeon, a rebellious colony in outer space.

Amuro’s wartime service is pretty much just a drawn-out series of tragedies, as he loses comrades, rivals and friends to the constant fighting, and is repeatedly subject to military discipline. Meanwhile, his pacifist mother rejects him, and his distant father spirals into dementia. There are very few upsides to Amuro’s time in the military.3

While Amuro does appear to be on the ‘right’ side, insofar as the Federation is opposed to an odious fascist-style movement in the colonies, a major theme of the series is brutalisation, and the effect of war on the individuals and the societies that fight, as the normative rules of peacetime are gradually broken down.

On a memorably bleak occasion, Amuro seeks out his mother’s home, and finds the place ransacked and full of drunken Federation soldiers, who beat him up: he doesn’t believe them when they tell him they did not find anyone there, and though Amuro later finds his mother safe, we are left with the lingering impression that Federation troops can’t be trusted, and lawlessness is becoming the new norm. By the second series, Zeta Gundam (1985), this disturbing trend has reached its logical conclusion, and now the Federation is the authoritarian menace, with the new protagonist Kamille finding himself on the same side as former (and future) villain Char Aznable.

Of the many Gundam series, perhaps the one that shows the horrors of war most acutely is Gundam: Thunderbolt (2015). Set during the events of the first series, it follows protagonists on both sides of the war, memorably depicting the ‘Living Dead Division,’ a squad of Zeon amputees whose severed nerves are directly wired into their machines, reducing their reaction times to give them an edge in combat.

One such amputee is Daryl Lorenz, a young boy who sacrifices his last limb for the sake of his comrades. Thunderbolt also features the surgeon who is forced to perform the operation, and subsequently loses her mind. It’s as powerful a depiction of wartime dehumanisation as you will find, showing human bodies and minds used up coldly and deliberately for no sane reason. As Daryl becomes quite literally disembodied, his machine becomes the only way he can experience the mobility he has lost, and his identity becomes inseparably tied to his role as a pilot.

Lessons of Darkness

To take a hard left turn - in 1992, Werner Herzog created one of the most remarkable war documentaries ever made: Lessons of Darkness (currently on Youtube). Filmed in Kuwait during the immediate aftermath of the Iraqi invasion and occupation, Lessons of Darkness is not a conventional informative documentary, so much as a work of art. It is a slow, stylised meditation not just on the Gulf War, but on war itself, and what Herzog sees as the destructive and irrational nature of humanity.

In the voiceover, Herzog adopts the tone of an alien observer, who bears witness to the chaos with an attitude of bemused detachment. He provides no context about the background of the war, and offers no insights or opinions.

The documentary consists heavily of footage with no commentary whatsoever, mostly filmed from helicopters. These are surely some of the most extraordinary, apocalyptic images ever put to film. Herzog shows us endless expanses of fire and smoke from the burning oil fields; lakes of spilled oil reflecting the sky like a mirror; desolate wastelands strewn with the husks of destroyed vehicles; titanic skeletons of bombed-out refineries and burst containers. We watch workers toil for what must be hours in scorching heat to put out fires and cap spills, only to light the overflow on fire again.

Most haunting, however, are the film’s interviews, of which there are only two. In the first, after showing us the inside of an interrogation chamber, and panning without comment over tables laden with improvised torture devices, Herzog shows us a woman who watched two of her sons tortured to death, and lost her voice from pleading. ‘She cannot tell her story, but still tries.’

Later, we see another woman with a young boy who has also lost the ability to speak, after a soldier stomped on his head during a house raid. ‘He has spoken only once since, and then he only said that he never wants to learn how to talk.’

AC6 and war

Armored Core 6 shows us nothing quite so distressing, and whereas Herzog does break from his detached perspective to show us human beings and to hear their painful testimonies, AC6 is remarkable not for its humanity, as for the distinct lack of it. Whereas every other Fromsoft game features recognisably humanoid characters, capable of triggering emotive responses from players, AC6 does not feature a single human portrait or character model.

Although its characters are voiced, and a fairly lively bunch, the only visual representation we have of any of them are their digital icons, which appear on mission screens when they communicate remotely. Other than that, we spend the entire game looking not at human beings, but at machines.

Indeed, the central character Ayre, a disembodied alien who exists as a kind of ghost in the machine, appears no less human than the rest of the cast, because from the player’s perspective, they are all equally ephemeral, represented only by visual abstractions and voices without faces. Indeed, if AC6’s pilots met in the flesh, it is doubtful that they would even recognise each other. This is a familiar theme from Gundam: when Amuro and Char, long-time rivals who have fought many times in their suits, cross paths aboard a neutral station, they don’t know each other, and exchange idle pleasantries before going their separate ways.

Likewise, AC6’s disembodiment is not just a quirk, but appears to be a deliberate stylistic choice, which plays into the story in a significant way. The player’s pilot is an amnesiac mercenary, and, like most pilots we encounter, is defined entirely by his work. He has no other identity, no history, no relationships to speak of, and even his callsign is not his own invention, but merely scavenged from a wrecked mech. He has no meaningful existence independent of his job, and thus no bodily life outside of his machine. For much of the game, he works for ruthless corporations, and switches sides with total indifference, working for one bloc one day, and another the next. His handler and others repeatedly refer to him with dehumanising language, describing him as an ‘attack dog,’ and using him as a pawn in their obscure agendas.

Like Herzog’s alien observer, this dehumanised pilot witnesses (and takes part in) destruction mindlessly, without context or understanding. Indeed, for much of the game’s first act, the player is doing the dirty work of corporations, helping them to root out native resistance to their ruthless exploitation of the planet Rubicon.

The resistance’s name - Rubicon Liberation Front - and their banner, which shows a fighter in a keffiyeh, has obvious geopolitical associations. Desert landscapes evocative of Herzog’s 1992 footage feature in several missions, and the storyline’s focus on corporate impunity and the cynical pillaging of resources is a familiar theme from the news. It’s also suggestive that many battles take place in towns and cities that are presumably inhabited, and though we are never informed as to whether our actions harm civilians, the implication is there (see also: HighFleet).

The game consciously plays on the player’s sense of alienation and moral unease, notably in the first clash with an AC (or Armored Core (tm) - these are the better class of mechs). The opposing pilot is a young rookie who is fighting for his life, and it never feels like the outcome of the battle is in doubt. ‘I just wanted to be like you,’ he says, before his feed cuts off abruptly and his life comes to an end.

The player’s sense of being a small, exploited cog in a brutal machine is reinforced by the world design, which seems calculated to induce something akin to agoraphobia (see also: Space Hulk: Deathwing). The surface of Rubicon teems with immense industrial infrastructure, and the player is made to feel constantly dwarfed by their surroundings, even though their AC towers over houses and cars. The power and mobility of the AC adds to the sense of detachment the player feels towards the world around them, and like Herzog’s helicopter, we are often in flight, seeing the devastation of war from a physical and emotive distance.

The incredible productive abilities of this futuristic society are almost utopian, which plays into a common theme in mecha: in animations like Evangelion and Gundam 00, there is no small measure of wonder at the potential of technology. The viewer is often invited to marvel at immaculate futuristic cities, space stations and so on, and it’s hard not to share the obvious enthusiasm of the artists and animators. This idealistic view of technology is no surprise, given the role of science and industry in Japan’s post-war revival.

However, the same enthusiasm is usually tempered with ambivalence: Gundam also sees peril in technology, with mobile suits, superweapons, autonomous drones, and brainwashed cyborgs representing the dark side of technology, which can just as easily become a tool of destruction and oppression, rather than creation and liberation.

In AC6’s setting - as in Herzog’s documentary - it’s hard to find many upsides to the proliferation of technology, which has only empowered humanity’s destructive side. The only humans we hear much about - fellow pilots - are generally jaded wage-slaves who kill for a living, and their in-game bios are littered with references to poverty and hardship. A number are ex-military, and there’s a sense that this is one of the few paths out of deprivation in this setting; many have also undergone dangerous surgeries to enhance their abilities as pilots, much like Gundam’s cyber-newtypes.

The most significant industries we hear about are weapons manufacturers, and warring over resources is the order of the day on Rubicon. None of this gives the impression of a Star Trek-style post-scarcity society: although the technological capacity for such is clearly there, it’s also clear that the wealth generated by this technology is concentrated in very few hands.

If anything, the setting feels dystopian rather than utopian, and accordingly, the player must complete AC6 multiple times - with each new playthrough adding new choices, challenges, and revelations - before arriving at anything even vaguely resembling a happy ending.

Without giving too much away, it’s worth noting that a major antagonistic force in the game is artificial intelligence, and AC6 in general feels surprisingly relevant to the various maladies of our current moment in history.

But honourable mention to Psycho Patrol R, which I’m told is very good. Friend of the publication Trip Harrison has written some great stuff about it.

MSG launched a whole new sub-genre, known as ‘real robot,’ contrasted with the more optimistic and escapist ‘super robot’ forerunners.

And he wasn’t in a great place to start off with. He’s heavily autistic-coded, as are many Gundam protagonists, and has suffered from abandonment and neglect since early childhood. Amuro was the original sad boy forced to get in a robot.

I would not necessarily say that MSG is good - it’s very dated and borderline unwatchable at times - but it’s interesting as a historical artifact of pop sci-fi, emerging around the same time as Star Wars but having a far more pessimistic outlook and tone, and it does have its moments as a drama, particularly towards the end of the series.

Awesome work. I really need to get around to the AC games — I think you're right that the genre in general and AC6 in particular are very well positioned to reflect our present-day maladies. And, of course, FromSoft definitely has a trustworthy pedigree when it comes to representing the bleakness of humanity's decline.

One of the things I most love about Psycho Patrol R (thanks for the shout-out, by the way!) is how it sarcastically downplays the visceral, documentary-friendly horrors of armed conflict to focus instead on the structural dysfunction that incentivizes it in the first place. God only knows when it'll get its full release, but I'll be glad to have this analysis to hand whenever it does.

This kind of narrative has been ringing less and less true for me due the Ukraine invasion honestly. We're seeing the horrors of war, but it's still obviously preferable to horrors of being invaded and occupied.